-

NOWHERE TO HIDE: Mpumalanga education department mumbles answers to over-the-top cost of a guardhouse facelift

NOWHERE TO HIDE: Mpumalanga education department mumbles answers to over-the-top cost of a guardhouse facelift

-

SCA rejects Vantage Goldfields appeal to dodge refunding SSC for failed shareholding purchase

SCA rejects Vantage Goldfields appeal to dodge refunding SSC for failed shareholding purchase

-

A R3m guardhouse, and the ballooning of renovation budget from R15m to R42m by Mpumalanga education officials

A R3m guardhouse, and the ballooning of renovation budget from R15m to R42m by Mpumalanga education officials

-

SMME ownership skewed on geography, gender and age

SMME ownership skewed on geography, gender and age

-

Black magic rocks Mpumalanga government offices

Black magic rocks Mpumalanga government offices

-

The health benefits of stokvels

The health benefits of stokvels

-

Mphoko approaches court to stop Choppies sale

Mphoko approaches court to stop Choppies sale

-

Cuba-trained doctor argues that NHI will works as the biggest employer, government, is already subsidising public servants

Cuba-trained doctor argues that NHI will works as the biggest employer, government, is already subsidising public servants

-

Manager in hung Mpumalanga council accused of politicking against ANC

Manager in hung Mpumalanga council accused of politicking against ANC

-

Prices of core staple foods must be reduced – PMBEJD

Prices of core staple foods must be reduced – PMBEJD

-

SSC clinches a hallmark R390m BEE deal from Neo Energy

SSC clinches a hallmark R390m BEE deal from Neo Energy

-

Another investment scam arrest in the Free State

Another investment scam arrest in the Free State

-

Municipal manager deflected SIU’s attention on his wrongdoing

Municipal manager deflected SIU’s attention on his wrongdoing

-

Our knowledge system assumes Africa is poor of knowledge of history, innovation and technology – Prof Segobye

Our knowledge system assumes Africa is poor of knowledge of history, innovation and technology – Prof Segobye

-

Sekhukhune council’s negligent losses increases to R64.4 million

Sekhukhune council’s negligent losses increases to R64.4 million

-

Mpumalanga MK Party ‘leader’ cries sexual harassment amid pressure to quit

Mpumalanga MK Party ‘leader’ cries sexual harassment amid pressure to quit

-

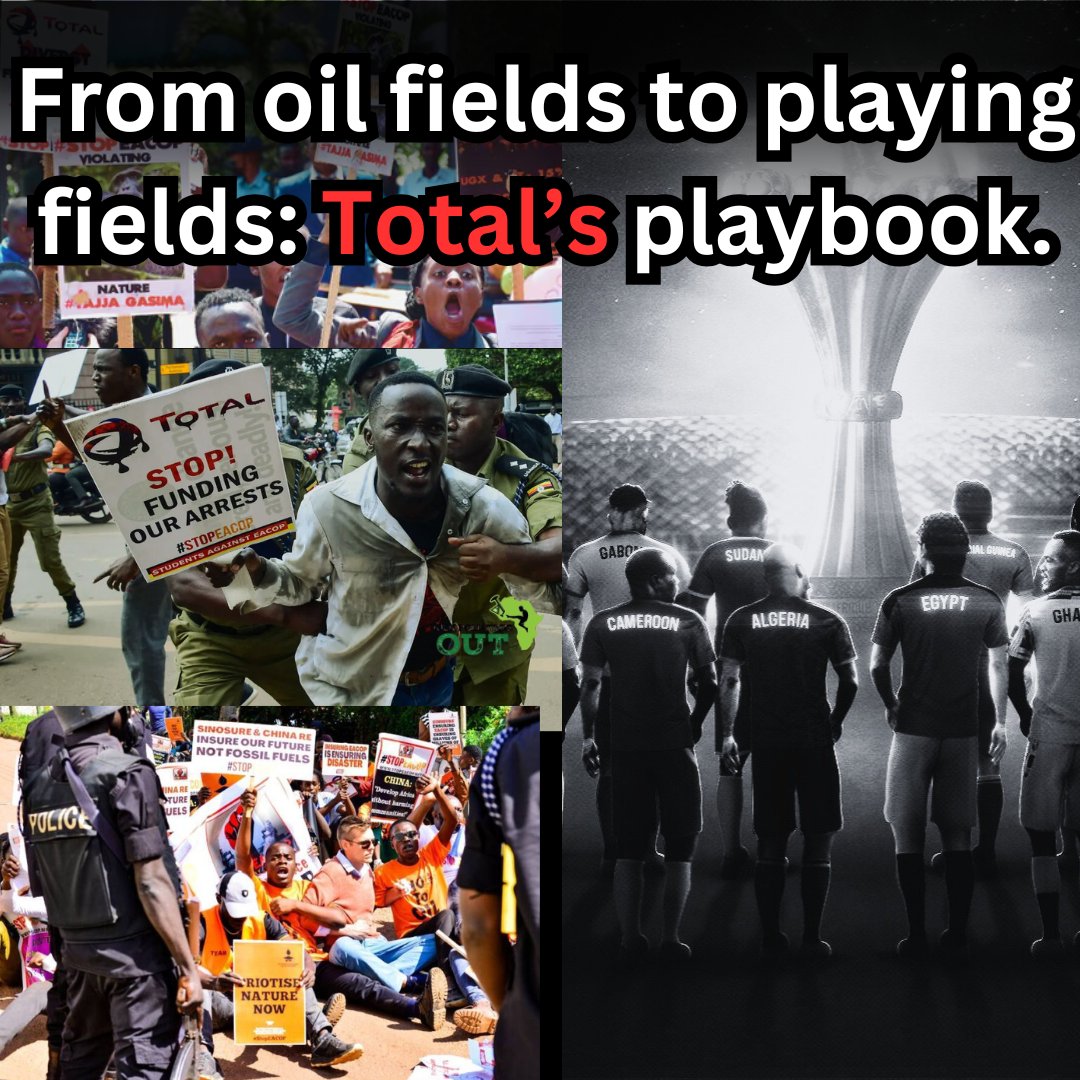

Sports federations should stop being a billboard for fossil fuel companies – activists

Sports federations should stop being a billboard for fossil fuel companies – activists

-

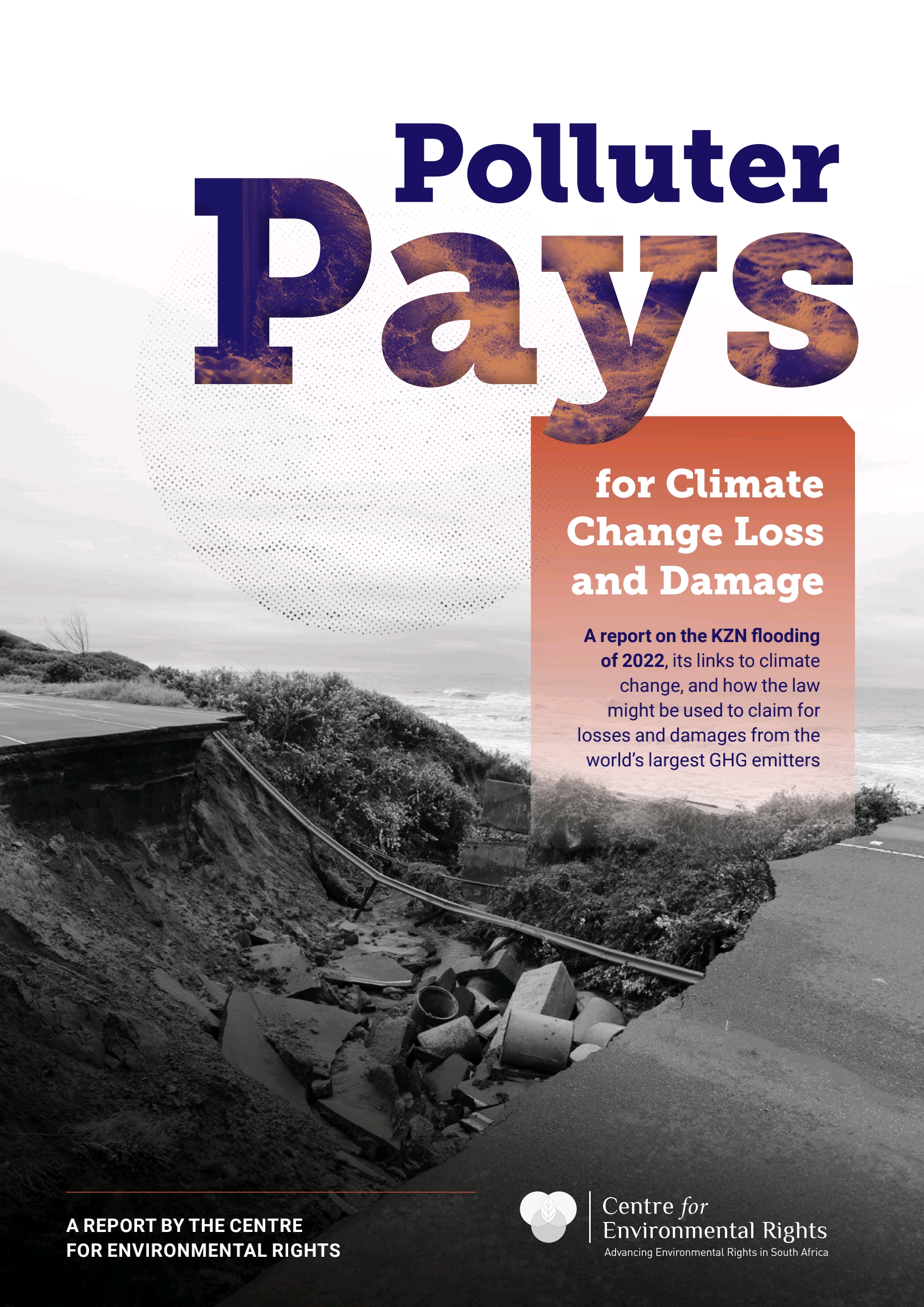

Polluters can be sued for climate change disasters – CER report

Polluters can be sued for climate change disasters – CER report

-

Northern Cape’s farm workers’ champion dies in car accident

Northern Cape’s farm workers’ champion dies in car accident

-

BRPs confident of Vision Investment’s rescue plan for Tongaat Hullet

BRPs confident of Vision Investment’s rescue plan for Tongaat Hullet

-

Businessman slaps Ronald Lamola, police and NPA with R5bn claim for unlawful arrest, detention and malicious prosecution

Businessman slaps Ronald Lamola, police and NPA with R5bn claim for unlawful arrest, detention and malicious prosecution

-

Free State Hawks pounce on ghost workers

Free State Hawks pounce on ghost workers

-

Business chamber calls for constructive engagement as Trump threatens to cut off financial aid to SA

Business chamber calls for constructive engagement as Trump threatens to cut off financial aid to SA

-

AU countries tap on the US$50 billion African market for medicines and vaccines

AU countries tap on the US$50 billion African market for medicines and vaccines

-

SA sits at position 47 of all countries affected by deadly air pollution

SA sits at position 47 of all countries affected by deadly air pollution

-

Opinion: Vision’s plan was approved without a competing business rescue plan after RGS mysteriously, but not surprisingly, withdrew

Opinion: Vision’s plan was approved without a competing business rescue plan after RGS mysteriously, but not surprisingly, withdrew

-

Polokwane municipality’s R41m ‘gift’ to a township developer

Polokwane municipality’s R41m ‘gift’ to a township developer

-

ANC infighting in Limpopo’s Waterberg region behind the tarnishing of MEC’s name

ANC infighting in Limpopo’s Waterberg region behind the tarnishing of MEC’s name

-

Electrical engineer slaps SIU and municipality with R1.8bn lawsuit

Electrical engineer slaps SIU and municipality with R1.8bn lawsuit

-

Govan Mbeki mayor still has more to answer

Govan Mbeki mayor still has more to answer

-

Toyota not living up to the Olympics Fair Play rule

Toyota not living up to the Olympics Fair Play rule

-

King Mswati III’s agents accused of poisoning exiled political activist

King Mswati III’s agents accused of poisoning exiled political activist

-

NPA’s panel likely to conduct further investigation before prosecuting on Lily Mine

NPA’s panel likely to conduct further investigation before prosecuting on Lily Mine

-

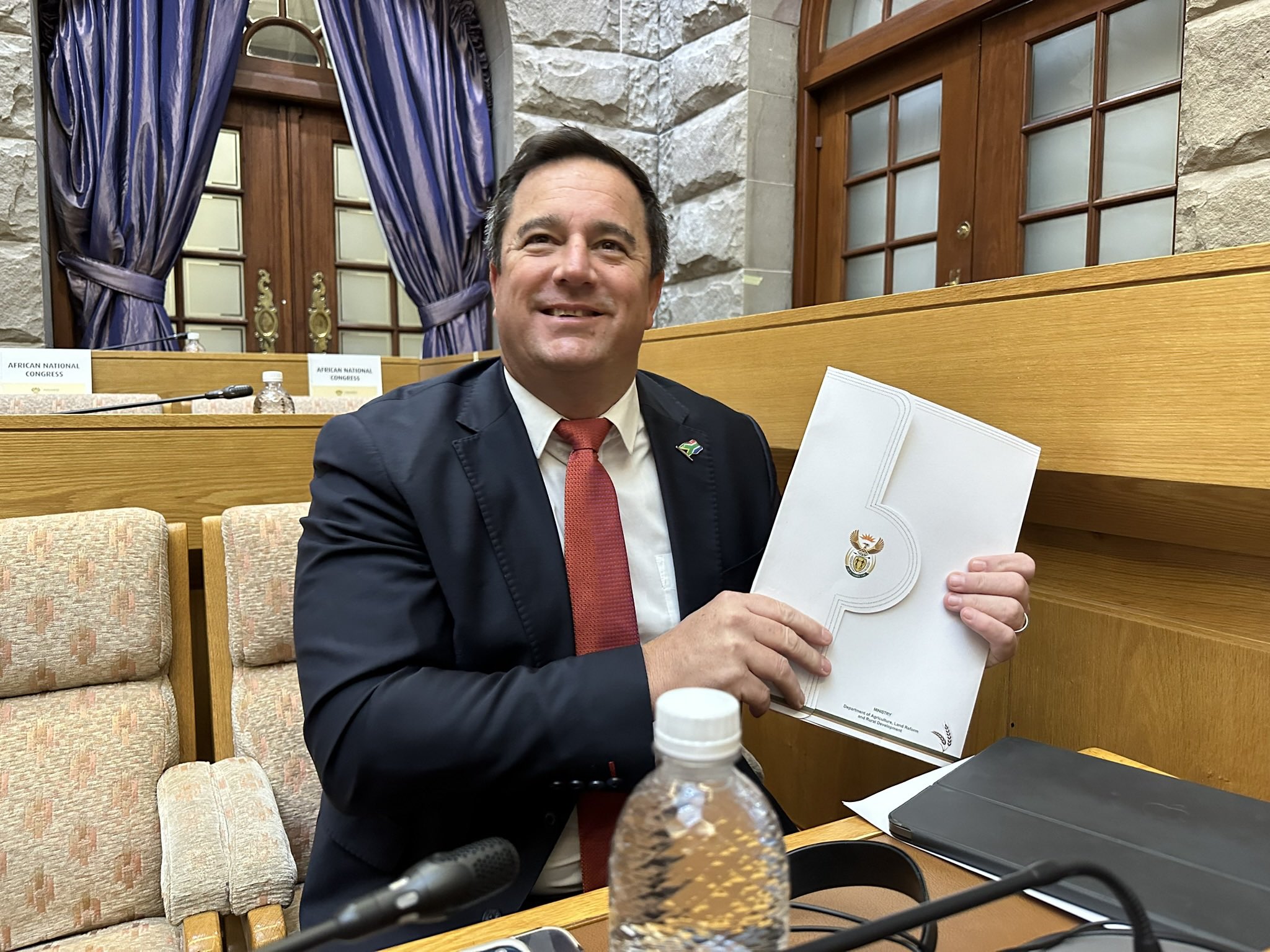

Didiza calls Steenhuisen to order on missing R500million

Didiza calls Steenhuisen to order on missing R500million

-

Limpopo DG used fake intelligence letter to fire spin doctor - Nehawu

Limpopo DG used fake intelligence letter to fire spin doctor - Nehawu

-

UCT student turns craving for kota into thriving business

UCT student turns craving for kota into thriving business

-

Macie shines spotlight on Mpumalanga political killings

Macie shines spotlight on Mpumalanga political killings

-

Government relegates landowners into children with amended law

Government relegates landowners into children with amended law

-

Ekurhuleni City’s finance MMC and CIO clash over billing system

Ekurhuleni City’s finance MMC and CIO clash over billing system

-

Four ANC-led provinces will have new premiers, besieged Phophi Ramathuba among them

Four ANC-led provinces will have new premiers, besieged Phophi Ramathuba among them

-

Drought has caused job losses in agriculture

Drought has caused job losses in agriculture

-

Hawks pounce on Thulamela municipal officials, confiscate electronic devices

Hawks pounce on Thulamela municipal officials, confiscate electronic devices

-

CETA to appear before Parliament on litany of allegations

-

Free State police act harshly on get-rich quick scammers

Free State police act harshly on get-rich quick scammers

-

UMP on a hunt for a vice-chancellor, UCT appoints acclaimed medicine scholar

UMP on a hunt for a vice-chancellor, UCT appoints acclaimed medicine scholar

-

SA company on track to complete biggest water treatment plant in SADC region

SA company on track to complete biggest water treatment plant in SADC region

-

Khato Civils delivers SADC’s largest Water Treatment Plant

Khato Civils delivers SADC’s largest Water Treatment Plant

-

R1.6 bn Eskom bill, R500m Chinese substation chokes Mpumalanga municipality until 2039

R1.6 bn Eskom bill, R500m Chinese substation chokes Mpumalanga municipality until 2039

-

UCT students’ call-up to the Springboks

UCT students’ call-up to the Springboks

-

Another racist murder in Delmas

Another racist murder in Delmas

-

Cubana Maritzburg to close down after landlord decides to accommodate government offices

Cubana Maritzburg to close down after landlord decides to accommodate government offices

-

Stumbling block out of Rachoene’s way to appoint Road Agency Limpopo board

Stumbling block out of Rachoene’s way to appoint Road Agency Limpopo board

-

Africa’s large economies are also the major air polluters accounting for 1.1 million premature deaths – report

Africa’s large economies are also the major air polluters accounting for 1.1 million premature deaths – report

-

Poor financial health may see more metros being downgraded by rating agencies – AG

Poor financial health may see more metros being downgraded by rating agencies – AG

-

Investment conference pledges massive green energy projects for Limpopo

Investment conference pledges massive green energy projects for Limpopo

-

Welcome to Sekhukhune district municipality where officials get into the bank account and transfer cash

Welcome to Sekhukhune district municipality where officials get into the bank account and transfer cash

-

‘Libyan military trainees are a threat to SA’s internal security’ – ISS

‘Libyan military trainees are a threat to SA’s internal security’ – ISS

-

Limpopo ANC PEC distances itself from Thabazimbi scuffle for power

Limpopo ANC PEC distances itself from Thabazimbi scuffle for power

-

DA-led coalition wins Thabazimbi after the ANC failed another court bid

DA-led coalition wins Thabazimbi after the ANC failed another court bid

-

SAMSA COO foisted BEE partner on bunkering company illegally – court confirms

SAMSA COO foisted BEE partner on bunkering company illegally – court confirms

-

Mpumalanga human settlements officials must be suspended for inflating prices - DA

Mpumalanga human settlements officials must be suspended for inflating prices - DA

-

Use of drugs to cope with unpleasant feelings rather than socialising lead adolescents to abuse – UCT study

Use of drugs to cope with unpleasant feelings rather than socialising lead adolescents to abuse – UCT study

-

MP Joe Maswanganyi's relative fails a Concourt bid to remain chief in Limpopo

MP Joe Maswanganyi's relative fails a Concourt bid to remain chief in Limpopo

-

Global entrepreneur Robert Gumede, partners make a sweet move by snatching top CEO for Tongaat Hullets

Global entrepreneur Robert Gumede, partners make a sweet move by snatching top CEO for Tongaat Hullets

-

MAMPARAGATE: Officials awarded tenders to the most expensive bidders

MAMPARAGATE: Officials awarded tenders to the most expensive bidders

-

Mpumalanga DG left his job as province became wilder again with shootings of officials

Mpumalanga DG left his job as province became wilder again with shootings of officials

-

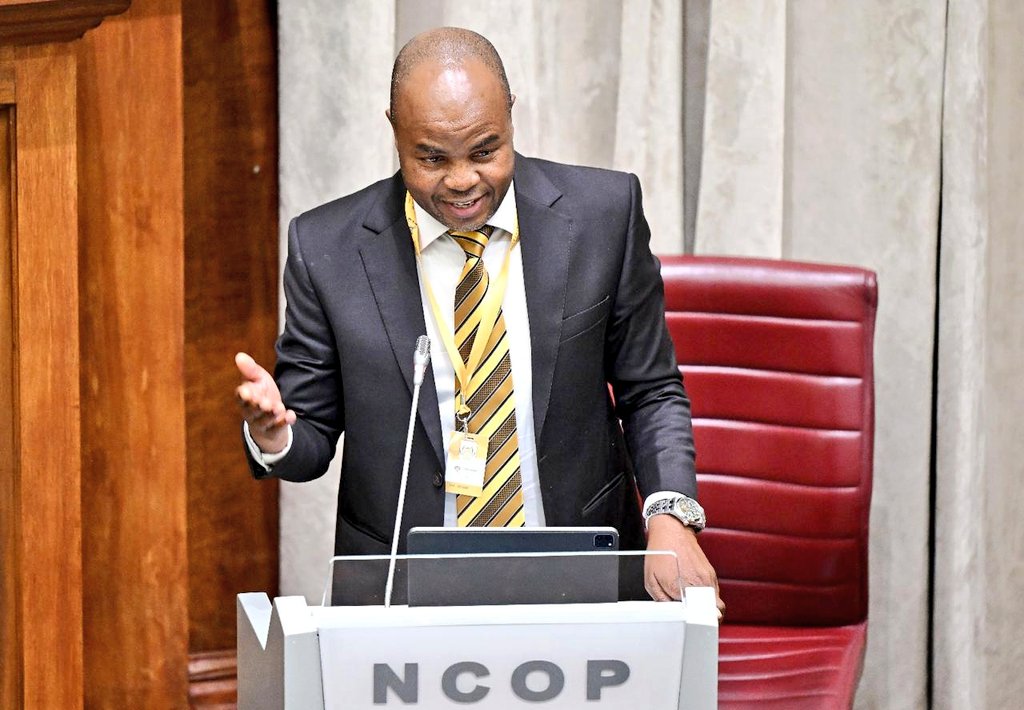

NCOP’s record vindicates electrical engineer on SIU’s claim of overcharging in electrification project

NCOP’s record vindicates electrical engineer on SIU’s claim of overcharging in electrification project

-

Directors shield acting CEO accused of flouting procurement processes and having a questionable status to work in SA

Directors shield acting CEO accused of flouting procurement processes and having a questionable status to work in SA

-

SSC Group acquires 100% shareholding of mine exploration giant

-

Basic Education’s legal team studying court judgment ordering the release of cheating learners’ results

Basic Education’s legal team studying court judgment ordering the release of cheating learners’ results

-

Municipality pays R131.6m to an irregularly appointed security company even after its illegal contract had expired

Municipality pays R131.6m to an irregularly appointed security company even after its illegal contract had expired

-

Former Zim vice-president leaves embattled son alone as he withdraws from a lawsuit against Welshman Ncube

Former Zim vice-president leaves embattled son alone as he withdraws from a lawsuit against Welshman Ncube

-

Bafana Bafana legend to lead UCT’s women’s team

Bafana Bafana legend to lead UCT’s women’s team

-

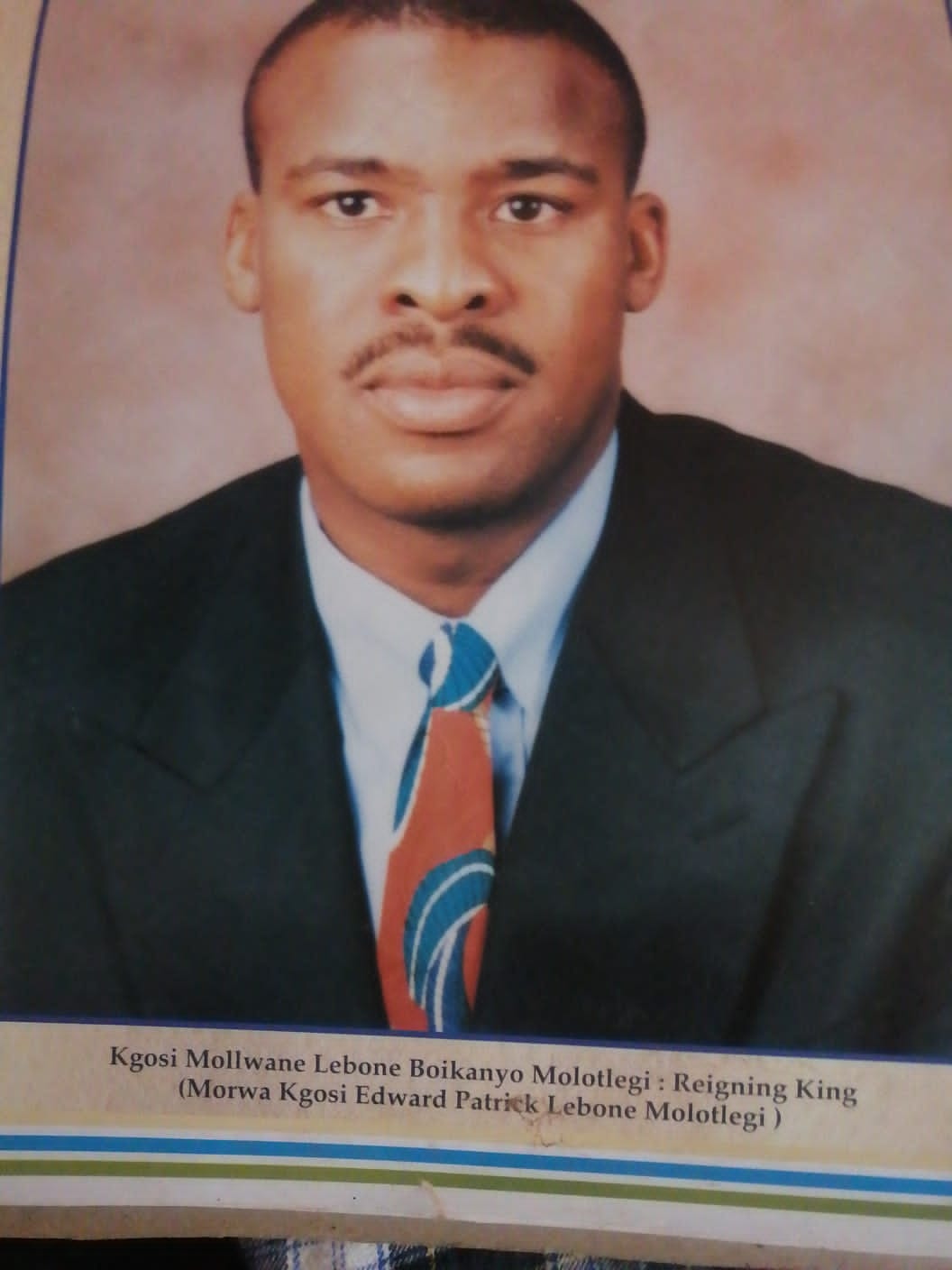

‘I want my abandoned siblings to be recognised in the royal family’ – Royal Bafokeng throne claimant

‘I want my abandoned siblings to be recognised in the royal family’ – Royal Bafokeng throne claimant

-

Mantashe’s son’s ‘appointment’ to a SETA board sees EFF MP thrown out of meeting

Mantashe’s son’s ‘appointment’ to a SETA board sees EFF MP thrown out of meeting

-

Even a modest VAT increase can have a devastating impact on low-income households

Even a modest VAT increase can have a devastating impact on low-income households

-

‘Take down defamatory posts or face litigation’ – MP education MEC warns Sedibe

‘Take down defamatory posts or face litigation’ – MP education MEC warns Sedibe

-

Limpopo DG must resign for abandoning report about a director who jazzed up his CV – Nehawu

Limpopo DG must resign for abandoning report about a director who jazzed up his CV – Nehawu

-

Businessman lost R184bn in wrongful prosecution – actuary report

Businessman lost R184bn in wrongful prosecution – actuary report

-

Tesla and BYD Auto still leading in the production of clean vehicles

Tesla and BYD Auto still leading in the production of clean vehicles

-

MEC distances herself from the loss of Northern Cape farm workers in equity schemes

MEC distances herself from the loss of Northern Cape farm workers in equity schemes

-

Outcry over R115 million budgeted for ‘tender cartel’s’ projects

Outcry over R115 million budgeted for ‘tender cartel’s’ projects

-

Loud silence on Lienbenberg’s startling allegations against Ramaphosa

Loud silence on Lienbenberg’s startling allegations against Ramaphosa

-

An accidental touch on a cellphone's screen and a missed call saved Eswatini’s politician’s life

An accidental touch on a cellphone's screen and a missed call saved Eswatini’s politician’s life

-

SOMETHING FISHY: Mpumalanga HOD’s house, car raided to ‘find a R3m stash’

SOMETHING FISHY: Mpumalanga HOD’s house, car raided to ‘find a R3m stash’

-

HPCSA’s disciplinary process unfair to Limpopo premier

HPCSA’s disciplinary process unfair to Limpopo premier

-

SCA vindicated under fire Limpopo Treasury MEC Kgabo Mahoai for Dirco payment

SCA vindicated under fire Limpopo Treasury MEC Kgabo Mahoai for Dirco payment

-

Engineering professor, Mulalo Doyoyo, posthumously awarded the Order of Mapungubwe

Engineering professor, Mulalo Doyoyo, posthumously awarded the Order of Mapungubwe

-

Black knights save Tongaat Hullet

Black knights save Tongaat Hullet

-

Mpumalanga department’s negligence cost it close to R100m

Mpumalanga department’s negligence cost it close to R100m

-

Countries must write cheques to match global warming loss and damage

Countries must write cheques to match global warming loss and damage

-

How white farmers used big Afrikaans to rob us of life-changing shares – Agri-BEE beneficiary

How white farmers used big Afrikaans to rob us of life-changing shares – Agri-BEE beneficiary

-

PPE corruption-linked Mpumalanga officials still have their jobs

PPE corruption-linked Mpumalanga officials still have their jobs

-

Audit committee finds many wrongs with Mopani EPWP programme, but municipality promises to act swiftly

Audit committee finds many wrongs with Mopani EPWP programme, but municipality promises to act swiftly

-

Zimbabwean patient is not part of the complaint against Premier Ramathuba

Zimbabwean patient is not part of the complaint against Premier Ramathuba

-

Mpumalanga EFF leader bats for 'undeserving' contractor, attacks graft-busting MEC

Mpumalanga EFF leader bats for 'undeserving' contractor, attacks graft-busting MEC

-

Engineer not worried by failure to review and set aside SIU’s ‘one-sided’ report

Engineer not worried by failure to review and set aside SIU’s ‘one-sided’ report

-

City of Mbombela manager in hot water

City of Mbombela manager in hot water

-

Mulaudzi rises from the ashes with a R2bn mining deal

Mulaudzi rises from the ashes with a R2bn mining deal

-

Murder scene, Covid-19 and nudity – this is how a Limpopo private school’s camp went

Murder scene, Covid-19 and nudity – this is how a Limpopo private school’s camp went

-

‘We will stop liquidation once we see the funds’ – SSC Group

‘We will stop liquidation once we see the funds’ – SSC Group

-

Law Society of Zimbabwe has failed to probe a complaint against Welshman Ncube

Law Society of Zimbabwe has failed to probe a complaint against Welshman Ncube

-

UMP leadership tarnishes institution with bloopers

UMP leadership tarnishes institution with bloopers

-

Foundation to introduce the ‘real chief’ of Royal Bafokeng

Foundation to introduce the ‘real chief’ of Royal Bafokeng

-

UCT signs agreement to train football administrators in Africa

-

Isilo’s threat to approach International Court ‘worrying and concerning’ – Didiza

Isilo’s threat to approach International Court ‘worrying and concerning’ – Didiza

-

The unknown engineer we snubbed has left us

The unknown engineer we snubbed has left us

-

Robert Gumede’s consortium declined to buy a vote for R600m

Robert Gumede’s consortium declined to buy a vote for R600m

-

Public Protector rejected a complaint that could have saved public resources

Public Protector rejected a complaint that could have saved public resources

-

Shambolic ABC Motsepe League matters highlighted in Parliament

Shambolic ABC Motsepe League matters highlighted in Parliament

-

Athletics SA president bought liquor using federation’s credit card

Athletics SA president bought liquor using federation’s credit card

-

‘Zuma dismissed me as a madman’ – claims whistleblower who brought evidence on Mpumalanga political killings

‘Zuma dismissed me as a madman’ – claims whistleblower who brought evidence on Mpumalanga political killings

-

VBS investigation must net every implicated individual irrespective of political status - SACP

VBS investigation must net every implicated individual irrespective of political status - SACP

-

EU must regulate monolithic FIFA bedevilled by patronage, indifference to human rights

EU must regulate monolithic FIFA bedevilled by patronage, indifference to human rights

-

Vision Investments unperturbed by shareholders vote, going ahead with plan to rescue THL

Vision Investments unperturbed by shareholders vote, going ahead with plan to rescue THL

-

Northern Cape government refuses to pay for investigation into fronting scam of farm workers

Northern Cape government refuses to pay for investigation into fronting scam of farm workers

-

CETA board evades questions on CEO’s tender ‘irregularities’

CETA board evades questions on CEO’s tender ‘irregularities’

-

Limpopo to develop and upgrade 36 construction companies

Limpopo to develop and upgrade 36 construction companies

-

Limpopo education challenges directive to pay R17m in teachers’ rural incentives

Limpopo education challenges directive to pay R17m in teachers’ rural incentives

-

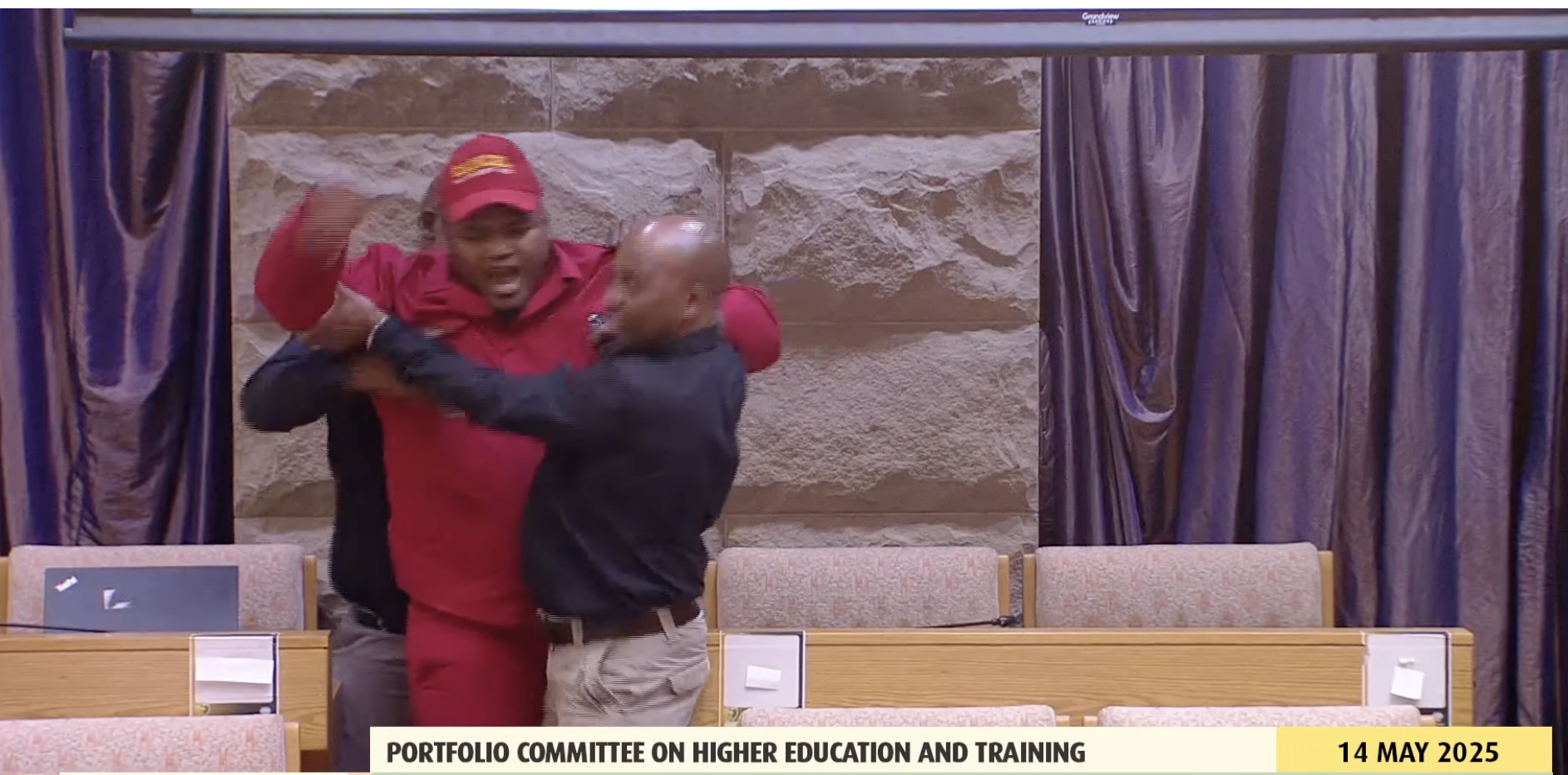

Release of files, minister’s bold acceptance of blame for Seta appointments’ fiasco and flaring of tempers

Release of files, minister’s bold acceptance of blame for Seta appointments’ fiasco and flaring of tempers

-

Tenders in the Musina-Makhado SEZ must be investigated - DA

Tenders in the Musina-Makhado SEZ must be investigated - DA

-

Mozambique elections: The Constitutional Council will fail

Mozambique elections: The Constitutional Council will fail

-

NPA still pursuing fraud case against deputy minister Bernice Swarts

NPA still pursuing fraud case against deputy minister Bernice Swarts

-

Mpumalanga premier’s R404.6 million headache

Mpumalanga premier’s R404.6 million headache

-

MEC goes to court to reverse CFO’s appointment in Mpumalanga’s capital city

MEC goes to court to reverse CFO’s appointment in Mpumalanga’s capital city

-

KZN MEC’s retiree friend the reason criminally accused mayor and speaker are not suspended

KZN MEC’s retiree friend the reason criminally accused mayor and speaker are not suspended

-

UN urges advertising agencies to cut ties with fossil fuel companies

UN urges advertising agencies to cut ties with fossil fuel companies

-

Mpumalanga HOD ‘swept damning investigation report under the carpet’

Mpumalanga HOD ‘swept damning investigation report under the carpet’

-

New government should not change land and agriculture policies

New government should not change land and agriculture policies

-

Scopa launches investigation into education tenders following The People’s Eye exposé

Scopa launches investigation into education tenders following The People’s Eye exposé

-

ANALYSIS: How Limpopo ANC avoided a massive downward spiral

ANALYSIS: How Limpopo ANC avoided a massive downward spiral

-

There is no need to review agricultural policy after May 29 – chief economist

There is no need to review agricultural policy after May 29 – chief economist

-

CETA board caves in to pressure and suspend domineering CEO

CETA board caves in to pressure and suspend domineering CEO

-

Outside chance for Makamu if tribalism becomes an issue in Limpopo premier candidate nomination

Outside chance for Makamu if tribalism becomes an issue in Limpopo premier candidate nomination

-

Officials held personally liable for payments to wrongfully appointed companies

Officials held personally liable for payments to wrongfully appointed companies

-

Summit to nudge Africa to take its place in refining clean technology minerals

Summit to nudge Africa to take its place in refining clean technology minerals

-

The jobless youth is becoming impatient – Premier Ramathuba

The jobless youth is becoming impatient – Premier Ramathuba

-

‘Prioritise child nutrition as a political decision’ – NGO

‘Prioritise child nutrition as a political decision’ – NGO

-

PA still committed to GNU – Chinelle Stevens

PA still committed to GNU – Chinelle Stevens

-

Will climate change denier Donald Trump’s election see the US pulling out of COP29?

Will climate change denier Donald Trump’s election see the US pulling out of COP29?

-

Unpacking the Indlulamithi South Africa Scenarios: Are We Truly in a Vulture Culture?

Unpacking the Indlulamithi South Africa Scenarios: Are We Truly in a Vulture Culture?

-

Mathabatha halts corruption-riddled recruitment process and launches an investigation

Mathabatha halts corruption-riddled recruitment process and launches an investigation

-

Mpumalanga’s Govan Mbeki municipality is a “base of corruption”

Mpumalanga’s Govan Mbeki municipality is a “base of corruption”

-

Was Polokwane mayor’s firearm used at Juju Valley election violence?

Was Polokwane mayor’s firearm used at Juju Valley election violence?

-

The future of AI is not about what the technology can do but also about who’s using it, and how – report

The future of AI is not about what the technology can do but also about who’s using it, and how – report

-

Mulaudzi’s Luvhomba Group signs arms deal with Chinese company

Mulaudzi’s Luvhomba Group signs arms deal with Chinese company

-

Engineer drags SIU to Concourt for abuse of power

Engineer drags SIU to Concourt for abuse of power

-

G20 in Rio: Elevating Africa's role to shape the future

G20 in Rio: Elevating Africa's role to shape the future

-

SAFLII questioned for changing a judgement in an on-going case

SAFLII questioned for changing a judgement in an on-going case

-

Deputy minister admits R500k debt but reneges promise to pay

Deputy minister admits R500k debt but reneges promise to pay

-

NPA lauded for agreement with McKinsey to repay R1.1bn benefited from state capture

NPA lauded for agreement with McKinsey to repay R1.1bn benefited from state capture

-

Zulu king’s prime minister mum about action against sexual harassment accuser, but threatens MEC

Zulu king’s prime minister mum about action against sexual harassment accuser, but threatens MEC

-

Wakkerstroom coal mine stalls as litigation continue for nearly a decade

Wakkerstroom coal mine stalls as litigation continue for nearly a decade

-

UCT researchers use cutting-edge technology to identify human remains

UCT researchers use cutting-edge technology to identify human remains

-

‘We did not bribe Limpopo MEC’ – Ivanplats Mine

-

Falsely charged businessman gradually crushing opponents to claim his multi-million rand assets

Falsely charged businessman gradually crushing opponents to claim his multi-million rand assets

-

Social grants not doing ANC any favour in these elections – UJ survey

Social grants not doing ANC any favour in these elections – UJ survey

-

The scourge of sexual harassment in SA’s tertiary institutions

The scourge of sexual harassment in SA’s tertiary institutions

-

Mpumalanga MEC sues EFF’s Collen Sedibe for defamation

Mpumalanga MEC sues EFF’s Collen Sedibe for defamation

-

Mpumalanga premier’s R10bn inheritance of unfinished, cash-guzzling projects and a lawsuit

Mpumalanga premier’s R10bn inheritance of unfinished, cash-guzzling projects and a lawsuit

-

Chamber inundated with calls from SA nationals taking up Trump’s offer

Chamber inundated with calls from SA nationals taking up Trump’s offer

-

Bongo sues government for R38.2 million

Bongo sues government for R38.2 million

-

Chiguvare accuses ‘bought’ opposition parties of hampering change in Zimbabwe

Chiguvare accuses ‘bought’ opposition parties of hampering change in Zimbabwe

-

SIU probes Mpumalanga education department over R15m maintenance projects

SIU probes Mpumalanga education department over R15m maintenance projects

-

‘Why is Public Works and Infrastructure deputy minister not stepping aside?’ asks businessman who laid a fraud charge in 2013

‘Why is Public Works and Infrastructure deputy minister not stepping aside?’ asks businessman who laid a fraud charge in 2013

-

.jpg) Elite Mpumalanga school fires whistleblowing director on R4m misappropriation

Elite Mpumalanga school fires whistleblowing director on R4m misappropriation

-

Stealthily, the cat with nine lives leaves the cage

Stealthily, the cat with nine lives leaves the cage

-

New technology to assist rural home and owners to reap financial rewards from their properties

New technology to assist rural home and owners to reap financial rewards from their properties

-

Msibi contemplates resigning from ANC due to ‘persistent persecution’

Msibi contemplates resigning from ANC due to ‘persistent persecution’

-

.jpg) Audit report exposes former executive for staging kidnapping to pay blacklisted buddy

Audit report exposes former executive for staging kidnapping to pay blacklisted buddy

-

MEC Rachoene announces R225m commitments by private sector to upgrade roads

MEC Rachoene announces R225m commitments by private sector to upgrade roads

-

Nzimande sat on a damning forensic report, wayward board members still off the hook four years later

Nzimande sat on a damning forensic report, wayward board members still off the hook four years later

-

Cryptocurrency scam suspect lied about closing his account after 'robbery at gunpoint'

Cryptocurrency scam suspect lied about closing his account after 'robbery at gunpoint'

-

Another major victory for entrepreneur as he fights to reclaim his assets after his acquittal

Another major victory for entrepreneur as he fights to reclaim his assets after his acquittal

-

Outcry as consulting tenders in Mpumalanga public works are awarded to foreign companies

Outcry as consulting tenders in Mpumalanga public works are awarded to foreign companies

-

In the mind of a young inventor

In the mind of a young inventor

-

‘My bank details were stolen to run crypto scam’ – says Sandile Unruly Matsheke

‘My bank details were stolen to run crypto scam’ – says Sandile Unruly Matsheke

-

Van Zyl vows to continue the fight against excessive bank interest rates

Van Zyl vows to continue the fight against excessive bank interest rates

-

MINING TRAUMA SERIES: Motsepe’s mine managers accused of snubbing DMRE advice to build a ventilation shaft on communal land

MINING TRAUMA SERIES: Motsepe’s mine managers accused of snubbing DMRE advice to build a ventilation shaft on communal land

-

Dear President Patrice Motsepe

Dear President Patrice Motsepe

-

Samwu blows whistleblower’s cover in R61.1m corruption, calls for charges against him

Samwu blows whistleblower’s cover in R61.1m corruption, calls for charges against him

-

Despite a R71.2 million surplus, KZN Film Commission's officials are under probe for malfeasance

Despite a R71.2 million surplus, KZN Film Commission's officials are under probe for malfeasance

-

Ndlovu moves past 60/40 gender equity hurdle in Mpumalanga cabinet, North-West’s Mokgosi still stuck

Ndlovu moves past 60/40 gender equity hurdle in Mpumalanga cabinet, North-West’s Mokgosi still stuck

-

ANC, Ekurhuleni council accused of dragging feet in disciplining police chief facing allegations of being a sex pest

ANC, Ekurhuleni council accused of dragging feet in disciplining police chief facing allegations of being a sex pest

-

Magaqa assassin’s sentencing is ‘justice abridged’ – Public Interest SA

Magaqa assassin’s sentencing is ‘justice abridged’ – Public Interest SA

-

Cryptocurrency scammers leave investors high and dry

Cryptocurrency scammers leave investors high and dry

-

Court dismisses ‘biased’ MEC’s decision to allow mining in a Mpumalanga wetland

Court dismisses ‘biased’ MEC’s decision to allow mining in a Mpumalanga wetland

-

Mpumalanga premier sues newspaper for defamation

Mpumalanga premier sues newspaper for defamation

-

‘Department approved inflated prices’ - bidder

‘Department approved inflated prices’ - bidder

-

Robert Gumede's consortium lays fraud charge on sugar bidding

Robert Gumede's consortium lays fraud charge on sugar bidding

-

Olympians take a hardline stance against Toyota for global warming and demand action from the IOC

Olympians take a hardline stance against Toyota for global warming and demand action from the IOC

-

Groblersdal police refuse to open a case against VBS-implicated Limpopo MEC

Groblersdal police refuse to open a case against VBS-implicated Limpopo MEC

-

Former deputy president David Mabuza must tell who killed my husband

Former deputy president David Mabuza must tell who killed my husband

-

‘Mmabana Foundation is a money-laundering scheme’ – North West DA

‘Mmabana Foundation is a money-laundering scheme’ – North West DA

-

Premier Mandla Ndlovu aiming at politicians’ killers

Premier Mandla Ndlovu aiming at politicians’ killers

-

‘There was nothing sinister’ – ANCYL treasurer-general Zwelo Masilela on NYDA interview

‘There was nothing sinister’ – ANCYL treasurer-general Zwelo Masilela on NYDA interview

-

Brace yourself for an ANC-led coalition – SRF Tracking Poll

Brace yourself for an ANC-led coalition – SRF Tracking Poll

-

ANC councillors in Dannhauser face Buthelezi’s wrath for reinstating a dismissed CFO

ANC councillors in Dannhauser face Buthelezi’s wrath for reinstating a dismissed CFO

-

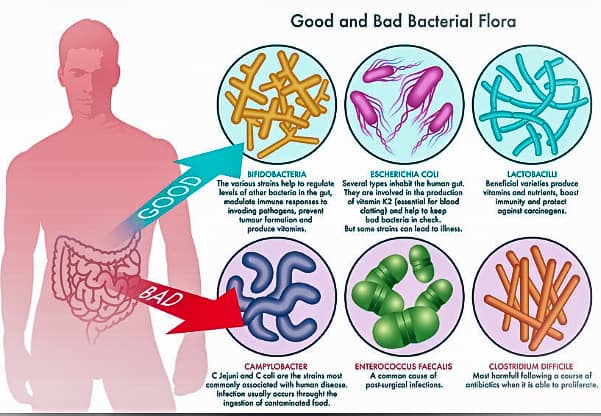

Resistance to antibiotics need special attention to save lives – experts

Resistance to antibiotics need special attention to save lives – experts

-

Mayor must resign for protecting rapist

Mayor must resign for protecting rapist

-

Outcry as Polokwane municipality awards tenders worth R331.2m to companies with tax issues

Outcry as Polokwane municipality awards tenders worth R331.2m to companies with tax issues

-

Mozambique elections: Talks are on the horizon

Mozambique elections: Talks are on the horizon

-

Disgraced Mozambican company bids afresh for Tongaat assets while Gumede’s consortium takes giant leap to finalise its take over

Disgraced Mozambican company bids afresh for Tongaat assets while Gumede’s consortium takes giant leap to finalise its take over

-

Polokwane mayor must review corruption-riddled tenders - ODCiSA

Polokwane mayor must review corruption-riddled tenders - ODCiSA

-

Energy Council’s partnership with state capture consultancy an affront

Energy Council’s partnership with state capture consultancy an affront

-

Deputy minister reneges promise to pay R500k debt and then withdraws application to gag businessman and a media house

Deputy minister reneges promise to pay R500k debt and then withdraws application to gag businessman and a media house

-

Mahindra, IDC explore establishing a KCD plant in SA

Mahindra, IDC explore establishing a KCD plant in SA

-

A contract that no one wants to talk about: Is Mpumalanga health department hiding something?

A contract that no one wants to talk about: Is Mpumalanga health department hiding something?

-

‘I’ll let bygones be bygones’ – Bongo after his discharge from fraud and money laundering case

‘I’ll let bygones be bygones’ – Bongo after his discharge from fraud and money laundering case

-

Khato Civil’s African dream

Khato Civil’s African dream

-

Free State Health HOD facing criminal charges has been demoted to be provincial accountant general.

Free State Health HOD facing criminal charges has been demoted to be provincial accountant general.

-

Mpumalanga’s R150 million expenditure ‘down the drain’

Mpumalanga’s R150 million expenditure ‘down the drain’

-

Samwu’s plan to vilify whisteblower of R61m corruption falls flat

Samwu’s plan to vilify whisteblower of R61m corruption falls flat

-

‘I’m not usurping amakhosi powers’ – Thoko Didiza

‘I’m not usurping amakhosi powers’ – Thoko Didiza

-

Welcome to Zolani Balekwa’s ‘artivism’

Welcome to Zolani Balekwa’s ‘artivism’

-

Being a forensic investigator in Mpumalanga is not for the faint-hearted

Being a forensic investigator in Mpumalanga is not for the faint-hearted

-

Engineer’s report motivates R3bn payment to an irregularly appointed company at Prasa

Engineer’s report motivates R3bn payment to an irregularly appointed company at Prasa

-

‘Courts must not gag MPs’ – pleads convicted Eswatini MP

‘Courts must not gag MPs’ – pleads convicted Eswatini MP

-

UCT research gives thumbs up to home language education

UCT research gives thumbs up to home language education

-

Border between Lesotho and South Africa is not porous but wide open

Border between Lesotho and South Africa is not porous but wide open

-

Municipalities could have spend R2m for councillors to attend ANC shindig

Municipalities could have spend R2m for councillors to attend ANC shindig

-

Sekhukhune municipality’s 127 million problems

Sekhukhune municipality’s 127 million problems

-

Phosa’s role in finding the Libyan billions

Phosa’s role in finding the Libyan billions

-

Mayors, municipal managers to be held personally liable for pollution of water resources

Mayors, municipal managers to be held personally liable for pollution of water resources

-

City of Matlosana manager did not steal R3m – investigation report

City of Matlosana manager did not steal R3m – investigation report

-

Sekhukhune municipality mum on lost R46.4 million

Sekhukhune municipality mum on lost R46.4 million

-

‘I’m not appealing’ – says Mandla Msibi after DC suspends him for three years

‘I’m not appealing’ – says Mandla Msibi after DC suspends him for three years

-

Lawyer accused of collapsing biggest citrus estate struck off the roll

Lawyer accused of collapsing biggest citrus estate struck off the roll

-

Mpumalanga Agriculture department’s attempt to dismiss a R65million claim fails

Mpumalanga Agriculture department’s attempt to dismiss a R65million claim fails

-

Mpumalanga premier to convince disillusioned PSL to consider bringing matches to Mbombela stadium

Mpumalanga premier to convince disillusioned PSL to consider bringing matches to Mbombela stadium

-

Northern Cape government wimps out of challenging R3.7m payment to an investigator of land scam

Northern Cape government wimps out of challenging R3.7m payment to an investigator of land scam

-

Ndlovu targets 5% economic growth for job creation in all sectors

Ndlovu targets 5% economic growth for job creation in all sectors

-

Fetakgomo Tubatse mayor, Eddie Maila, takes keen interest in improving education

Fetakgomo Tubatse mayor, Eddie Maila, takes keen interest in improving education

-

Mpumalanga Public Works HOD on the ropes after adverse Scopa findings

Mpumalanga Public Works HOD on the ropes after adverse Scopa findings

-

Mpumalanga capital city CFO fights new attempts to suspend her

Mpumalanga capital city CFO fights new attempts to suspend her

-

Mathebula’s ever rising star as a tennis coach

Mathebula’s ever rising star as a tennis coach

-

Village diesel producer’s breakthrough as he gets his first big order

Village diesel producer’s breakthrough as he gets his first big order

-

Limpopo DPP orders police to reinvestigate false CV case against senior civil servant

Limpopo DPP orders police to reinvestigate false CV case against senior civil servant

-

Municipal manager ordered to stop sewerage spill into river or face a prison sentence

Municipal manager ordered to stop sewerage spill into river or face a prison sentence

-

Vindicated businessman wins first leg of the fight against Master of the High Court to reclaim his assets and cash

Vindicated businessman wins first leg of the fight against Master of the High Court to reclaim his assets and cash

-

Shot Mpumalanga activist raised legitimate concern: workers milked coffers in overtime claims

Shot Mpumalanga activist raised legitimate concern: workers milked coffers in overtime claims

-

SA company set to begin construction of R5.7bn Malawi water project

SA company set to begin construction of R5.7bn Malawi water project

-

Manzini must release details on Mpox – DA

Manzini must release details on Mpox – DA

-

KZN flood victims have a chance to set a precedent by suing fossil-fuel companies for the climate change disaster

KZN flood victims have a chance to set a precedent by suing fossil-fuel companies for the climate change disaster

-

KZN, Mpumalanga governments take steps to resolve chieftaincy disputes

KZN, Mpumalanga governments take steps to resolve chieftaincy disputes

-

ARB concludes that TotalEnergies’ sponsorship of SANParks is greenwashing

ARB concludes that TotalEnergies’ sponsorship of SANParks is greenwashing

-

Deputy minister Bernice Swarts’s fraud case still under investigation - NPA

Deputy minister Bernice Swarts’s fraud case still under investigation - NPA

-

LPC to investigate law firm for ‘unverified’ AI information use

LPC to investigate law firm for ‘unverified’ AI information use

-

Msibi to appeal his suspension from the ANC

Msibi to appeal his suspension from the ANC

-

Ramaphosa calls the private sector to invest in major infrastructure projects

Ramaphosa calls the private sector to invest in major infrastructure projects

-

Msibi resigns as MPL as Luthuli House upholds his suspension

Msibi resigns as MPL as Luthuli House upholds his suspension

-

Creecy slammed for being lenient to Sasol

Creecy slammed for being lenient to Sasol

-

Mantashe’s neglect haunts him as mining company drags him to court

Mantashe’s neglect haunts him as mining company drags him to court

-

Forex trading couple’s R2.9m house attached after they defrauded investors

Forex trading couple’s R2.9m house attached after they defrauded investors

-

Zimbabwe is at crossroads – Pastor Mapfumo-Chiguvare

Zimbabwe is at crossroads – Pastor Mapfumo-Chiguvare

-

Hawks ward off a potential food poisoning disaster

Hawks ward off a potential food poisoning disaster

-

G20 Presidency is SA’s stepping stone to create an electric vehicles industry in SADC

G20 Presidency is SA’s stepping stone to create an electric vehicles industry in SADC

-

A 30-second video-recording may save Msibi on misconduct charges

A 30-second video-recording may save Msibi on misconduct charges

-

ANC defends premier against R100 million theft allegations

ANC defends premier against R100 million theft allegations

-

Big construction companies must empower, certify subcontractors to enable their growth - Khato Civils CEO

Big construction companies must empower, certify subcontractors to enable their growth - Khato Civils CEO

-

Teflon KZN mayor promoted to legislature

Teflon KZN mayor promoted to legislature

-

Premier Ndlovu’s ambitions: 300k jobs, 3% economic growth, R50bn investment and new adventure tourism projects

Premier Ndlovu’s ambitions: 300k jobs, 3% economic growth, R50bn investment and new adventure tourism projects

-

Businessman acquitted in a lengthy trial not yet out of the woods as he fights ‘corrupt’ Master of the High Court officials

Businessman acquitted in a lengthy trial not yet out of the woods as he fights ‘corrupt’ Master of the High Court officials

-

Two Limpopo teachers convicted for doing business with the education department

Two Limpopo teachers convicted for doing business with the education department

-

KZN Cogta MEC locked out of a facility managed by irregularly appointed former mayor’s wife

KZN Cogta MEC locked out of a facility managed by irregularly appointed former mayor’s wife

-

SMU council chairperson, CFO accused of taking kickbacks from 2 000-bed contractor

SMU council chairperson, CFO accused of taking kickbacks from 2 000-bed contractor

-

Welcome to Belfast where coal mining fields have bred killing fields

Welcome to Belfast where coal mining fields have bred killing fields

-

Corruption-fighting politician-cum-civil servant among those whose assets were attached for Covid-19 corruption

Corruption-fighting politician-cum-civil servant among those whose assets were attached for Covid-19 corruption

-

One Mpumalanga MEC to be axed to meet ANC’s gender balance guidelines

One Mpumalanga MEC to be axed to meet ANC’s gender balance guidelines

-

JUST IN: Gen Masemola suspends Mpumalanga commissioner on additional charges of misconduct

JUST IN: Gen Masemola suspends Mpumalanga commissioner on additional charges of misconduct

-

Limpopo capital city’s tale of ‘hiding’ a forensic report, wish to write off R34m due to financial mismanagement

Limpopo capital city’s tale of ‘hiding’ a forensic report, wish to write off R34m due to financial mismanagement

-

Odds stacked against expelled MK Party commander as he tries to remove Zuma

Odds stacked against expelled MK Party commander as he tries to remove Zuma

-

Fetakgomo Tubatse SEZ to bring new skills, technology and innovation – Mayor

Fetakgomo Tubatse SEZ to bring new skills, technology and innovation – Mayor

-

Court uplifts Mpumalanga provincial commissioner’s suspension again

Court uplifts Mpumalanga provincial commissioner’s suspension again

-

Robert Gumede’s Guma Group, HPX to develop R94.5bn rail network to link Liberia and Guinea

Robert Gumede’s Guma Group, HPX to develop R94.5bn rail network to link Liberia and Guinea

-

Grade 12 cheating rocks Mpumalanga as 150 learners are implicated

Grade 12 cheating rocks Mpumalanga as 150 learners are implicated

-

No levies must be paid to chiefs’ – ConCourt

No levies must be paid to chiefs’ – ConCourt

-

Botswana averts G7’s plan to certify diamond products in Antwerp

Botswana averts G7’s plan to certify diamond products in Antwerp

-

Beyond imagination

Beyond imagination

-

Controversial former mayor’s wife in KZN ‘given’ another job after fleeing previous employment

Controversial former mayor’s wife in KZN ‘given’ another job after fleeing previous employment

-

Free State Health HOD still not suspended four years since criminally charged

Free State Health HOD still not suspended four years since criminally charged

-

How the Matsamo CPA changed wrong perception that blacks cannot run commercial farms

How the Matsamo CPA changed wrong perception that blacks cannot run commercial farms

-

Mahlangu slowly turning things around to revive MEGA

Mahlangu slowly turning things around to revive MEGA

-

Official in Mpumalanga government’s corruption-busting unit dies after being shot 29 times

Official in Mpumalanga government’s corruption-busting unit dies after being shot 29 times

-

AI disinformation: human worse than detection software in distinguishing real and AI-generated content

AI disinformation: human worse than detection software in distinguishing real and AI-generated content

-

‘Come back home’ – Ramathuba’s plea to Limpopo-born professionals

‘Come back home’ – Ramathuba’s plea to Limpopo-born professionals

-

Relief as Ithala is saved from liquidation

Relief as Ithala is saved from liquidation

-

Dismantle organised producers of poisonous foods – human rights lawyers

Dismantle organised producers of poisonous foods – human rights lawyers

-

Board to finally account for employing a Swazi national and invalid hiring of a law firm

Board to finally account for employing a Swazi national and invalid hiring of a law firm

-

Motion to remove a mayor in Mpumalanga aims to portray the ANC as a loser before elections – provincial ANC secretary

Motion to remove a mayor in Mpumalanga aims to portray the ANC as a loser before elections – provincial ANC secretary

-

Limpopo premier Stanley Mathabatha’s ‘henchman’ arrested for faking CV

Limpopo premier Stanley Mathabatha’s ‘henchman’ arrested for faking CV

-

The dire state of the ABC Motsepe League

The dire state of the ABC Motsepe League

-

Dingaan Thobela’s death should serve as a kick in the butt for boxing authorities

Dingaan Thobela’s death should serve as a kick in the butt for boxing authorities

-

New Moz opposition party, Podemos, takes its parliamentary seats

New Moz opposition party, Podemos, takes its parliamentary seats

-

Climate-change marine heatwaves triple, cause expensive damage

Climate-change marine heatwaves triple, cause expensive damage

-

Data collected for Census 2022 unfit for purpose - UCT

Data collected for Census 2022 unfit for purpose - UCT

-

Nehawu needs explanation following withdrawal of charges against Limpopo official

Nehawu needs explanation following withdrawal of charges against Limpopo official

Village diesel producer’s breakthrough as he gets his first big order

Sizwe sama Yende

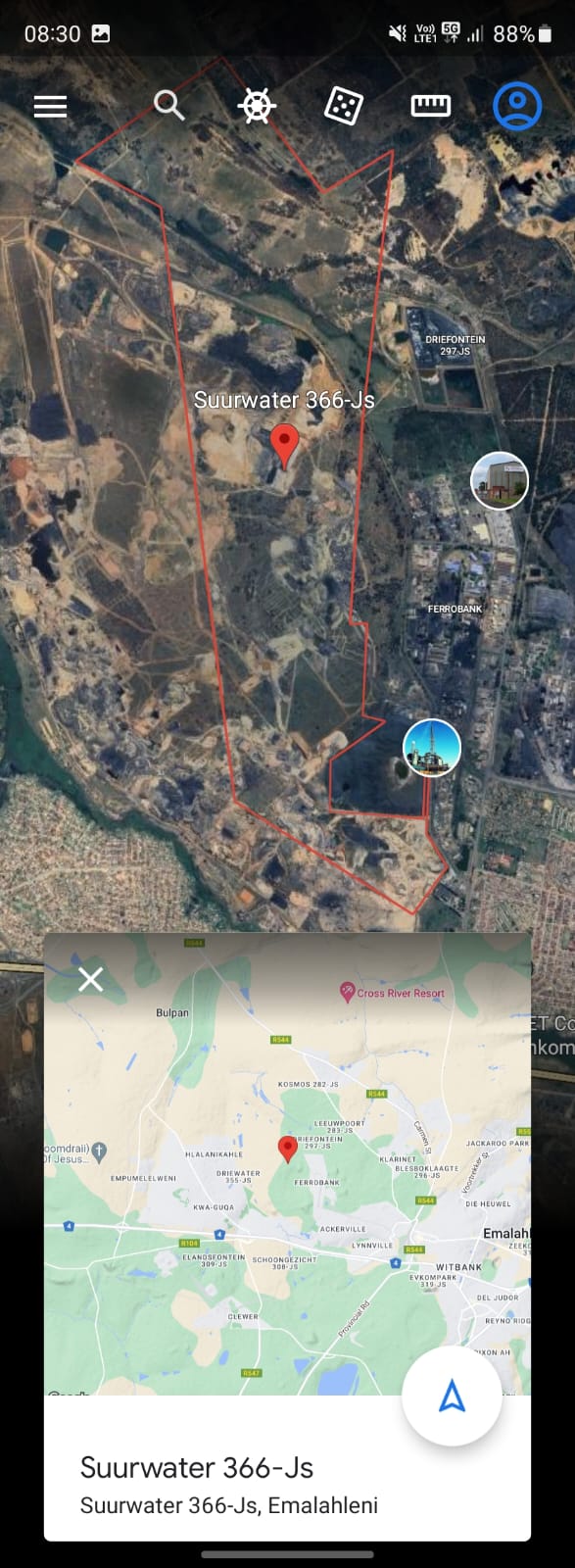

Israel Bhila’s site at Mangweni village near Komatipoort may look untidy and cluttered with plastics, bottles, coal dough and rusty homemade machines. It is however a promising and big diesel factory under construction.

A passerby on the R571 road to Mananga border post, along which the 38-year-old’s makeshift factory is situated, may not know something big is happening on the site until he gets closer and ask. This is a site of lofty dreams where Bhila is slowly building a diesel factory.

Bhila converts plastic waste into diesel. Since he started in 2017, he had been selling to locals after he tested the diesel on his truck and found out that it worked properly. His big break has only come recently after a Gauteng-based company contracted him to produce 900 000 litres a month after it was impressed by laboratory results of his diesel.

“It’s a tall order,” Bhila tells The People’s Eye, “but I’ve renegotiated to produce 100 000 litres for now as I try to increase my capacity over the next few months.”

Bhila’s diesel-making project started by chance. He was collecting waste for recycling in 2012 when he met a Chinese national in Maputo, Mozambique, who was in the business of exporting waste to China. The Chinese man connected Bhila to his brother-in-law in China, who told him via email that he was in the business of converting waste into energy. Bhila’s mind then shifted from just being a waste recycler to being a diesel producer.

Bhila explains that the plastic-to-diesel conversion is done through a process called pyrolysis, in which carbon-based materials are heated at extremely high temperatures (about 500°C) in the absence of oxygen and other reactive gases to produce combustible gases that are condensed into combustible liquid (fuel).

He started the project at home with the support of the Chinese man who taught him everything from heating to distilling.

Before the Covid-19 outbreak and lockdown in 2020, Bhila was producing 2 000 litres of diesel and petrol per day. He has been knocking on the doors of various financial institutions for help.

The University of Mpumalanga assisted him to send samples of his pyrolysis products to a laboratory owned by Swiss testing and certification services company SGS, where they were tested and certified in 2021. The Nkomazi Local Municipality gave him six hectares of land to build his factory.

At that time, the Small Enterprise Development Agency drafted his business plan and found that he would need R14 million to establish a diesel-producing plant.

Venda-born and US-educated engineer, inventor and academic, Professor Mulalo Doyoyo, said that government’s efforts were not aggressive enough to support innovation in the country. Doyoyo has many innovations behind his name, the latest being an eco-friendly liquid cement.

“The government should create fertile ground for innovation in all the provinces,” Doyoyo said. “Innovation agencies and structures such as the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research and special economic zones should be available in all corners. The thing about innovation is that you do not plan to innovate, sometimes it’s by accident, and innovators must have access to support,” he added.

Doyoyo said that once the ground was fertile and innovations come about, the country would create jobs. He said that South Africa needed an innovation think-tank with experts from all over the world to create this fertile ground.

He said that poverty was a stimulant for innovation, as witnessed in the US in the 1930s. “During the Great Depression in the US, many inventors popped up; our situation could be a motivation too,” he said. The Great Depression saw the invention of the helicopter, parking meter, walkie-talkie (two-way radio) and electric guitar, as well as xerography (dry photocopying).