-

Hawks pounce on Mpumalanga government officials in another repairs and maintenance scandal

Hawks pounce on Mpumalanga government officials in another repairs and maintenance scandal

-

Mulaudzi files R5bn claim against the state

Mulaudzi files R5bn claim against the state

-

Evaluation Board reinstates disputed value on Rupert’s Mpumalanga property

Evaluation Board reinstates disputed value on Rupert’s Mpumalanga property

-

Arqomanzi accused of delaying Lily Mine sale because it’s eyeing R141m profit from loan claim

Arqomanzi accused of delaying Lily Mine sale because it’s eyeing R141m profit from loan claim

-

Matric cheating rocks Mpumalanga once again

Matric cheating rocks Mpumalanga once again

-

Mvianga dismisses Royal Bafokeng’s response to his court application

Mvianga dismisses Royal Bafokeng’s response to his court application

-

ANC denies ever raising funds from City of Matlosana

ANC denies ever raising funds from City of Matlosana

-

‘SA must boycott the World Cup’ – Malema

‘SA must boycott the World Cup’ – Malema

-

Transnet loses third court battle and ordered to pay R60m to Gijima

Transnet loses third court battle and ordered to pay R60m to Gijima

-

UMP’s ambition to position SA as a leading rice exporter

UMP’s ambition to position SA as a leading rice exporter

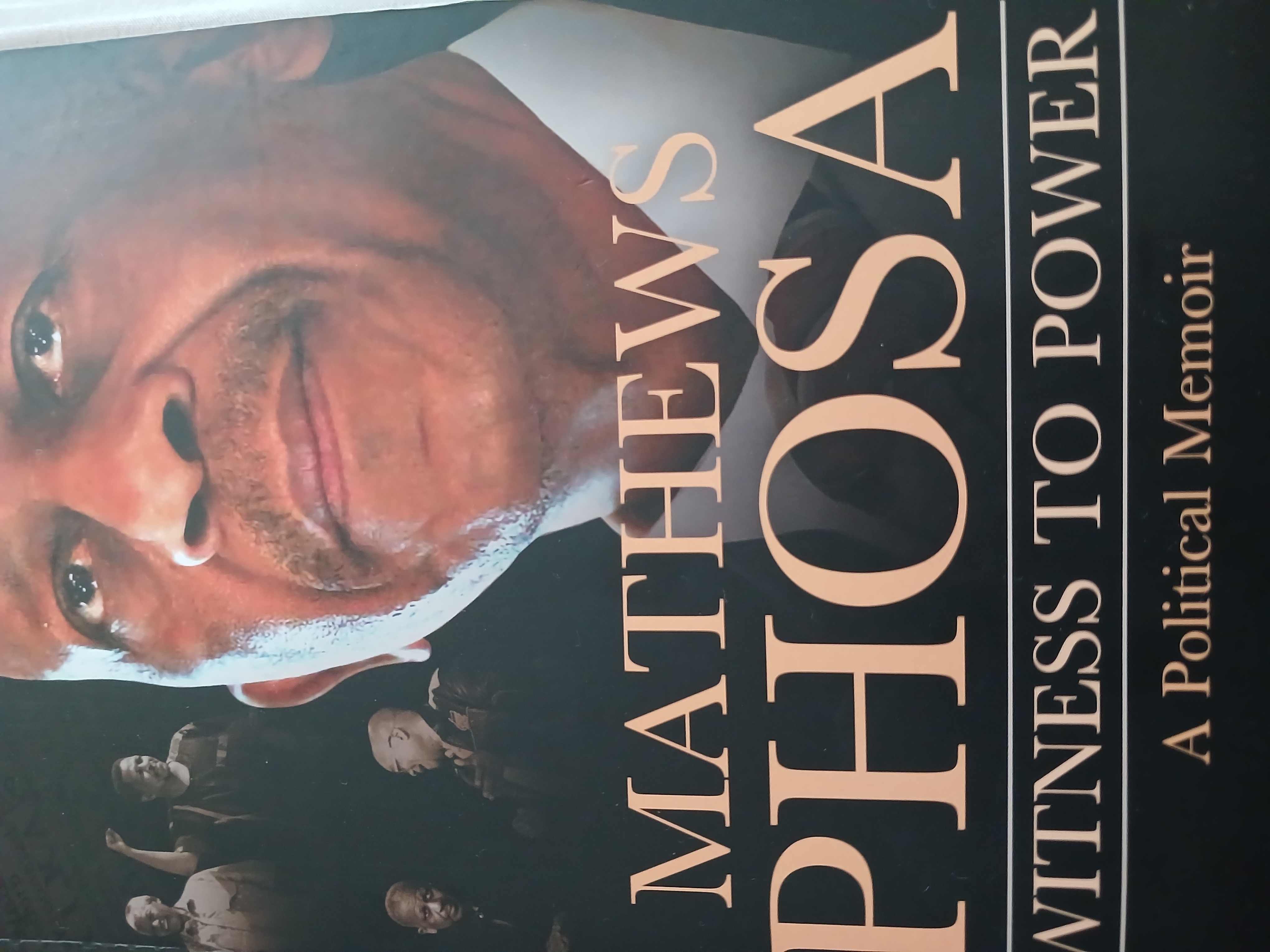

Phosa’s role in finding the Libyan billions

Sizwe sama Yende

The story of the mission Libyan billions, allegedly hidden by later dictator Muammar Gadaffi, was just another legend.

This is according to ANC veteran, Mathews Phosa, who recently published a political memoir – Witness to Power – which gives an account of his odyssey as an attorney, anti-apartheid activist, exile, and being part of the negotiating team for the transition from apartheid to democracy and serving in government and the ANC in the democratic era.

Phosa wrote that he was deeply involved in facilitating a meeting between Gadaffi’s opponents, the National Transitional Council (NTC), and then president, Jacob Zuma. The NTC wanted Zuma to broker peace and negotiations between them and Gadaffi.

After the Libyan civil war that resulted in Gadaffi’s assassination at his hometown, Sirte, on October 20 2011, a delegation of four Libyan citizens requested a meeting with him through an ANC intelligence official in 2012.

Phosa indicated that the delegation showed him a letter they had written to then ANC secretary-general, Gwede Mantashe, to pass to Zuma requesting a meeting to discuss what they called ‘the missing Libyan billions.’

“To me it sounded like the story of King Solomon’s Mines or the legend of the missing Kruger Millions,” he wrote.

The Libya Review reported recently that after the fall of Gaddafi’s regime, the new Libyan authorities launched an international investigation to recover Libyan assets worldwide, especially in East and Southern Africa.

Investigators were tracking around $100 billion. The investigation was, however, abandoned after a few months due to a lack of cooperation from the target countries.

The search resumed in 2023, the Libyan Review reported, and investigators had opened inquiries in West African nations, including Mali, Senegal, and Guinea, as well as in South Africa and Kenya, where the Libyan funds are purportedly hidden.

“Investigators fear that these funds could be used to support money laundering networks, particularly in West Africa. Enhanced financial monitoring is underway in countries like Senegal, Guinea, and Mali to trace the source of invested funds.”

Phosa said that he met Zuma at Mahlamba Ndlopfu the same evening following his meeting with the Libyans at Piccolo Mondo in Sandton.

He was surprised that Zuma had not received the letter. “I then showed him a copy of the letter. He appeared surprised, shocked even, and uneasy,” Phosa said.

“I recommended that he avoid meeting the delegation until we could gather more information to ascertain their credibility We needed to know whether they were genuine and whether they were at the right level to engage with Zuma as a president and head of state. I suggested that Siyabonga Cwele, as minister of state security, meet with them first.”

Zuma, Phosa said, seemed to agree with all that he had said but something else happened. “My security team told me that while I was inside discussing the matter with the president, the very same Libyan delegation had been ushered in to another office of the residence, apparently for a meeting with Zuma. I was taken aback,” he said.

Phosa said that after a year he received a delegation from the United States and they produced business cards indicating that they worked for the Central Intelligence Agency. They were also looking for the missing Libyan billions and had been in contact with the Libyan delegation.

Phosa said he told them that he was no longer in the ANC executive or government and would no longer be involved in the matter.

“But they would not let up. They understood the funds to be in a South African bank account. They were adamant but were unable to give me any details,” he said.

The US delegation said then secretary of state, John Kerry, would call Phosa to vouch for them but he did not.

Phosa then said that he would phone Reserve Bank governor, Lesetja Kganyago, to find out if he knew anything about a bank account in South Africa that held the Libyan billions. Kganyago asked Phosa to give him the account numbers and he would collect the money and send it back to Libya.

When Phosa said he did not have the account numbers, Kganyago replied: “Well, when you have them, give me the numbers and I will go and collect the funds, and if possible and if everything checks out and is above board, I can pass it over to the Libyan government. Other than that, there is no issue from the South African Reserve bank.”

Phosa wrote that there was a runour that the Libyan money had been in Zuma’s Nkandla residence and was then quietly moved to the Central Bank of Swaziland.

Phosa said he checked with his source in central bank and the investigation drew a blank. “While the whole affair remains shrouded in mystery, it certainly made my Libyan experience more interesting,” he said.