-

A R3m guardhouse, and the ballooning of renovation budget from R15m to R42m by Mpumalanga education officials

A R3m guardhouse, and the ballooning of renovation budget from R15m to R42m by Mpumalanga education officials

-

Black magic rocks Mpumalanga government offices

Black magic rocks Mpumalanga government offices

-

Manager in hung Mpumalanga council accused of politicking against ANC

Manager in hung Mpumalanga council accused of politicking against ANC

-

Our knowledge system assumes Africa is poor of knowledge of history, innovation and technology – Prof Segobye

Our knowledge system assumes Africa is poor of knowledge of history, innovation and technology – Prof Segobye

-

Sports federations should stop being a billboard for fossil fuel companies – activists

Sports federations should stop being a billboard for fossil fuel companies – activists

-

Polluters can be sued for climate change disasters – CER report

Polluters can be sued for climate change disasters – CER report

-

Northern Cape’s farm workers’ champion dies in car accident

Northern Cape’s farm workers’ champion dies in car accident

-

BRPs confident of Vision Investment’s rescue plan for Tongaat Hullet

BRPs confident of Vision Investment’s rescue plan for Tongaat Hullet

-

Businessman slaps Ronald Lamola, police and NPA with R5bn claim for unlawful arrest, detention and malicious prosecution

Businessman slaps Ronald Lamola, police and NPA with R5bn claim for unlawful arrest, detention and malicious prosecution

-

Free State Hawks pounce on ghost workers

Free State Hawks pounce on ghost workers

-

AU countries tap on the US$50 billion African market for medicines and vaccines

AU countries tap on the US$50 billion African market for medicines and vaccines

-

SA sits at position 47 of all countries affected by deadly air pollution

SA sits at position 47 of all countries affected by deadly air pollution

-

Opinion: Vision’s plan was approved without a competing business rescue plan after RGS mysteriously, but not surprisingly, withdrew

Opinion: Vision’s plan was approved without a competing business rescue plan after RGS mysteriously, but not surprisingly, withdrew

-

Electrical engineer slaps SIU and municipality with R1.8bn lawsuit

Electrical engineer slaps SIU and municipality with R1.8bn lawsuit

-

Toyota not living up to the Olympics Fair Play rule

Toyota not living up to the Olympics Fair Play rule

-

NPA’s panel likely to conduct further investigation before prosecuting on Lily Mine

NPA’s panel likely to conduct further investigation before prosecuting on Lily Mine

-

Didiza calls Steenhuisen to order on missing R500million

Didiza calls Steenhuisen to order on missing R500million

-

Limpopo DG used fake intelligence letter to fire spin doctor - Nehawu

Limpopo DG used fake intelligence letter to fire spin doctor - Nehawu

-

UCT student turns craving for kota into thriving business

UCT student turns craving for kota into thriving business

-

Ekurhuleni City’s finance MMC and CIO clash over billing system

Ekurhuleni City’s finance MMC and CIO clash over billing system

-

Four ANC-led provinces will have new premiers, besieged Phophi Ramathuba among them

Four ANC-led provinces will have new premiers, besieged Phophi Ramathuba among them

-

Hawks pounce on Thulamela municipal officials, confiscate electronic devices

Hawks pounce on Thulamela municipal officials, confiscate electronic devices

-

Free State police act harshly on get-rich quick scammers

Free State police act harshly on get-rich quick scammers

-

UMP on a hunt for a vice-chancellor, UCT appoints acclaimed medicine scholar

UMP on a hunt for a vice-chancellor, UCT appoints acclaimed medicine scholar

-

SA company on track to complete biggest water treatment plant in SADC region

SA company on track to complete biggest water treatment plant in SADC region

-

Another racist murder in Delmas

Another racist murder in Delmas

-

Cubana Maritzburg to close down after landlord decides to accommodate government offices

Cubana Maritzburg to close down after landlord decides to accommodate government offices

-

Africa’s large economies are also the major air polluters accounting for 1.1 million premature deaths – report

Africa’s large economies are also the major air polluters accounting for 1.1 million premature deaths – report

-

‘Libyan military trainees are a threat to SA’s internal security’ – ISS

‘Libyan military trainees are a threat to SA’s internal security’ – ISS

-

Limpopo ANC PEC distances itself from Thabazimbi scuffle for power

Limpopo ANC PEC distances itself from Thabazimbi scuffle for power

-

DA-led coalition wins Thabazimbi after the ANC failed another court bid

DA-led coalition wins Thabazimbi after the ANC failed another court bid

-

SAMSA COO foisted BEE partner on bunkering company illegally – court confirms

SAMSA COO foisted BEE partner on bunkering company illegally – court confirms

-

Mpumalanga human settlements officials must be suspended for inflating prices - DA

Mpumalanga human settlements officials must be suspended for inflating prices - DA

-

Use of drugs to cope with unpleasant feelings rather than socialising lead adolescents to abuse – UCT study

Use of drugs to cope with unpleasant feelings rather than socialising lead adolescents to abuse – UCT study

-

MP Joe Maswanganyi's relative fails a Concourt bid to remain chief in Limpopo

MP Joe Maswanganyi's relative fails a Concourt bid to remain chief in Limpopo

-

Mpumalanga DG left his job as province became wilder again with shootings of officials

Mpumalanga DG left his job as province became wilder again with shootings of officials

-

SSC Group acquires 100% shareholding of mine exploration giant

-

Basic Education’s legal team studying court judgment ordering the release of cheating learners’ results

Basic Education’s legal team studying court judgment ordering the release of cheating learners’ results

-

Former Zim vice-president leaves embattled son alone as he withdraws from a lawsuit against Welshman Ncube

Former Zim vice-president leaves embattled son alone as he withdraws from a lawsuit against Welshman Ncube

-

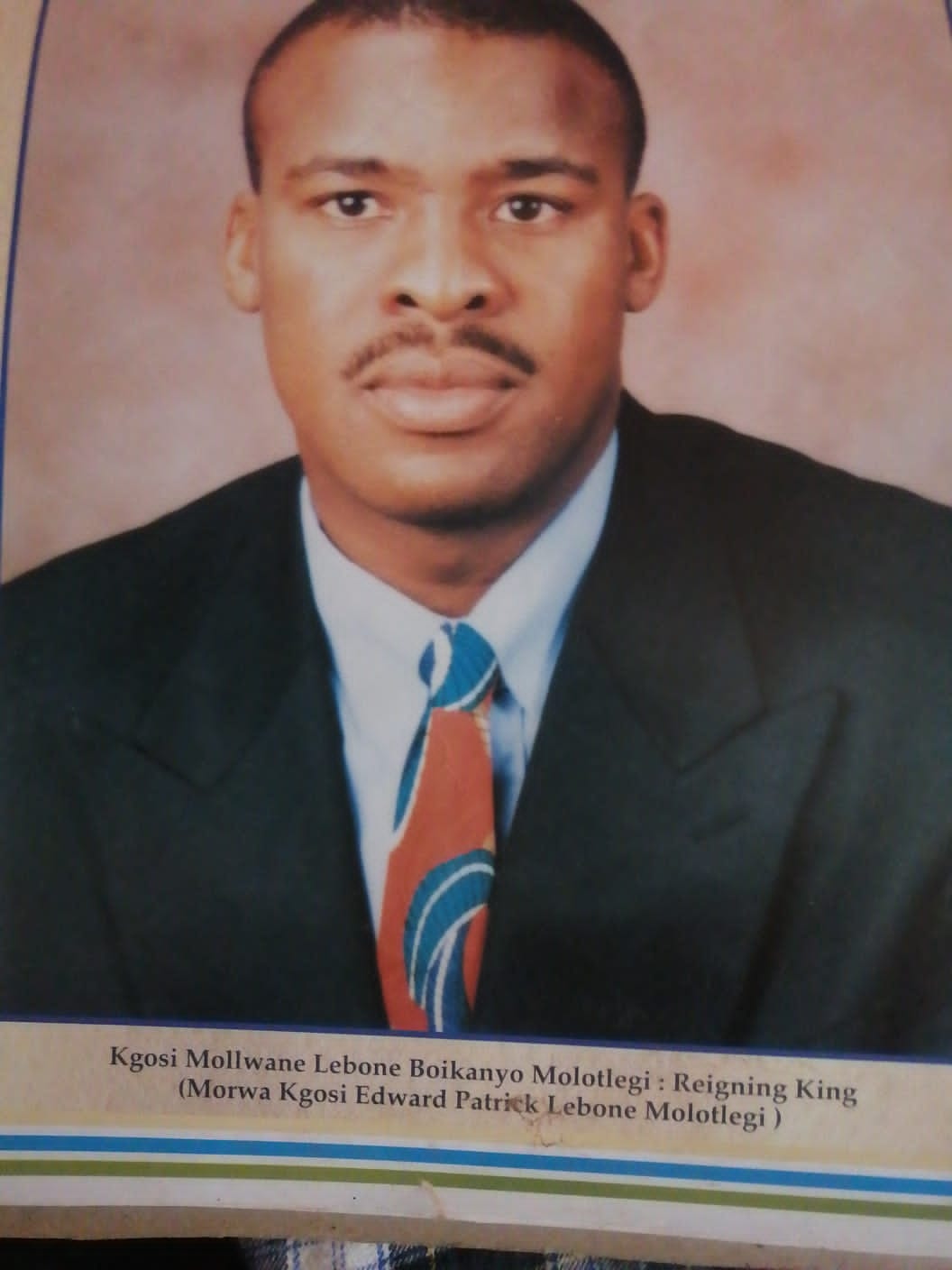

‘I want my abandoned siblings to be recognised in the royal family’ – Royal Bafokeng throne claimant

‘I want my abandoned siblings to be recognised in the royal family’ – Royal Bafokeng throne claimant

-

Limpopo DG must resign for abandoning report about a director who jazzed up his CV – Nehawu

Limpopo DG must resign for abandoning report about a director who jazzed up his CV – Nehawu

-

Tesla and BYD Auto still leading in the production of clean vehicles

Tesla and BYD Auto still leading in the production of clean vehicles

-

MEC distances herself from the loss of Northern Cape farm workers in equity schemes

MEC distances herself from the loss of Northern Cape farm workers in equity schemes

-

Loud silence on Lienbenberg’s startling allegations against Ramaphosa

Loud silence on Lienbenberg’s startling allegations against Ramaphosa

-

SOMETHING FISHY: Mpumalanga HOD’s house, car raided to ‘find a R3m stash’

SOMETHING FISHY: Mpumalanga HOD’s house, car raided to ‘find a R3m stash’

-

SCA vindicated under fire Limpopo Treasury MEC Kgabo Mahoai for Dirco payment

SCA vindicated under fire Limpopo Treasury MEC Kgabo Mahoai for Dirco payment

-

Engineering professor, Mulalo Doyoyo, posthumously awarded the Order of Mapungubwe

Engineering professor, Mulalo Doyoyo, posthumously awarded the Order of Mapungubwe

-

How white farmers used big Afrikaans to rob us of life-changing shares – Agri-BEE beneficiary

How white farmers used big Afrikaans to rob us of life-changing shares – Agri-BEE beneficiary

-

PPE corruption-linked Mpumalanga officials still have their jobs

PPE corruption-linked Mpumalanga officials still have their jobs

-

Audit committee finds many wrongs with Mopani EPWP programme, but municipality promises to act swiftly

Audit committee finds many wrongs with Mopani EPWP programme, but municipality promises to act swiftly

-

Engineer not worried by failure to review and set aside SIU’s ‘one-sided’ report

Engineer not worried by failure to review and set aside SIU’s ‘one-sided’ report

-

Mulaudzi rises from the ashes with a R2bn mining deal

Mulaudzi rises from the ashes with a R2bn mining deal

-

Law Society of Zimbabwe has failed to probe a complaint against Welshman Ncube

Law Society of Zimbabwe has failed to probe a complaint against Welshman Ncube

-

Foundation to introduce the ‘real chief’ of Royal Bafokeng

Foundation to introduce the ‘real chief’ of Royal Bafokeng

-

UCT signs agreement to train football administrators in Africa

-

Isilo’s threat to approach International Court ‘worrying and concerning’ – Didiza

Isilo’s threat to approach International Court ‘worrying and concerning’ – Didiza

-

The unknown engineer we snubbed has left us

The unknown engineer we snubbed has left us

-

Robert Gumede’s consortium declined to buy a vote for R600m

Robert Gumede’s consortium declined to buy a vote for R600m

-

Public Protector rejected a complaint that could have saved public resources

Public Protector rejected a complaint that could have saved public resources

-

VBS investigation must net every implicated individual irrespective of political status - SACP

VBS investigation must net every implicated individual irrespective of political status - SACP

-

Vision Investments unperturbed by shareholders vote, going ahead with plan to rescue THL

Vision Investments unperturbed by shareholders vote, going ahead with plan to rescue THL

-

Northern Cape government refuses to pay for investigation into fronting scam of farm workers

Northern Cape government refuses to pay for investigation into fronting scam of farm workers

-

CETA board evades questions on CEO’s tender ‘irregularities’

CETA board evades questions on CEO’s tender ‘irregularities’

-

Limpopo education challenges directive to pay R17m in teachers’ rural incentives

Limpopo education challenges directive to pay R17m in teachers’ rural incentives

-

NPA still pursuing fraud case against deputy minister Bernice Swarts

NPA still pursuing fraud case against deputy minister Bernice Swarts

-

Mpumalanga premier’s R404.6 million headache

Mpumalanga premier’s R404.6 million headache

-

MEC goes to court to reverse CFO’s appointment in Mpumalanga’s capital city

MEC goes to court to reverse CFO’s appointment in Mpumalanga’s capital city

-

UN urges advertising agencies to cut ties with fossil fuel companies

UN urges advertising agencies to cut ties with fossil fuel companies

-

New government should not change land and agriculture policies

New government should not change land and agriculture policies

-

ANALYSIS: How Limpopo ANC avoided a massive downward spiral

ANALYSIS: How Limpopo ANC avoided a massive downward spiral

-

There is no need to review agricultural policy after May 29 – chief economist

There is no need to review agricultural policy after May 29 – chief economist

-

CETA board caves in to pressure and suspend domineering CEO

CETA board caves in to pressure and suspend domineering CEO

-

Outside chance for Makamu if tribalism becomes an issue in Limpopo premier candidate nomination

Outside chance for Makamu if tribalism becomes an issue in Limpopo premier candidate nomination

-

Summit to nudge Africa to take its place in refining clean technology minerals

Summit to nudge Africa to take its place in refining clean technology minerals

-

‘Prioritise child nutrition as a political decision’ – NGO

‘Prioritise child nutrition as a political decision’ – NGO

-

PA still committed to GNU – Chinelle Stevens

PA still committed to GNU – Chinelle Stevens

-

Mathabatha halts corruption-riddled recruitment process and launches an investigation

Mathabatha halts corruption-riddled recruitment process and launches an investigation

-

Mulaudzi’s Luvhomba Group signs arms deal with Chinese company

Mulaudzi’s Luvhomba Group signs arms deal with Chinese company

-

SAFLII questioned for changing a judgement in an on-going case

SAFLII questioned for changing a judgement in an on-going case

-

Deputy minister admits R500k debt but reneges promise to pay

Deputy minister admits R500k debt but reneges promise to pay

-

Zulu king’s prime minister mum about action against sexual harassment accuser, but threatens MEC

Zulu king’s prime minister mum about action against sexual harassment accuser, but threatens MEC

-

Wakkerstroom coal mine stalls as litigation continue for nearly a decade

Wakkerstroom coal mine stalls as litigation continue for nearly a decade

-

UCT researchers use cutting-edge technology to identify human remains

UCT researchers use cutting-edge technology to identify human remains

-

Social grants not doing ANC any favour in these elections – UJ survey

Social grants not doing ANC any favour in these elections – UJ survey

-

‘Why is Public Works and Infrastructure deputy minister not stepping aside?’ asks businessman who laid a fraud charge in 2013

‘Why is Public Works and Infrastructure deputy minister not stepping aside?’ asks businessman who laid a fraud charge in 2013

-

.jpg) Elite Mpumalanga school fires whistleblowing director on R4m misappropriation

Elite Mpumalanga school fires whistleblowing director on R4m misappropriation

-

Msibi contemplates resigning from ANC due to ‘persistent persecution’

Msibi contemplates resigning from ANC due to ‘persistent persecution’

-

.jpg) Audit report exposes former executive for staging kidnapping to pay blacklisted buddy

Audit report exposes former executive for staging kidnapping to pay blacklisted buddy

-

Cryptocurrency scam suspect lied about closing his account after 'robbery at gunpoint'

Cryptocurrency scam suspect lied about closing his account after 'robbery at gunpoint'

-

New Africa Trade Unit leader aims to urge African entrepreneurs to invest outside their countries

New Africa Trade Unit leader aims to urge African entrepreneurs to invest outside their countries

-

‘My bank details were stolen to run crypto scam’ – says Sandile Unruly Matsheke

‘My bank details were stolen to run crypto scam’ – says Sandile Unruly Matsheke

-

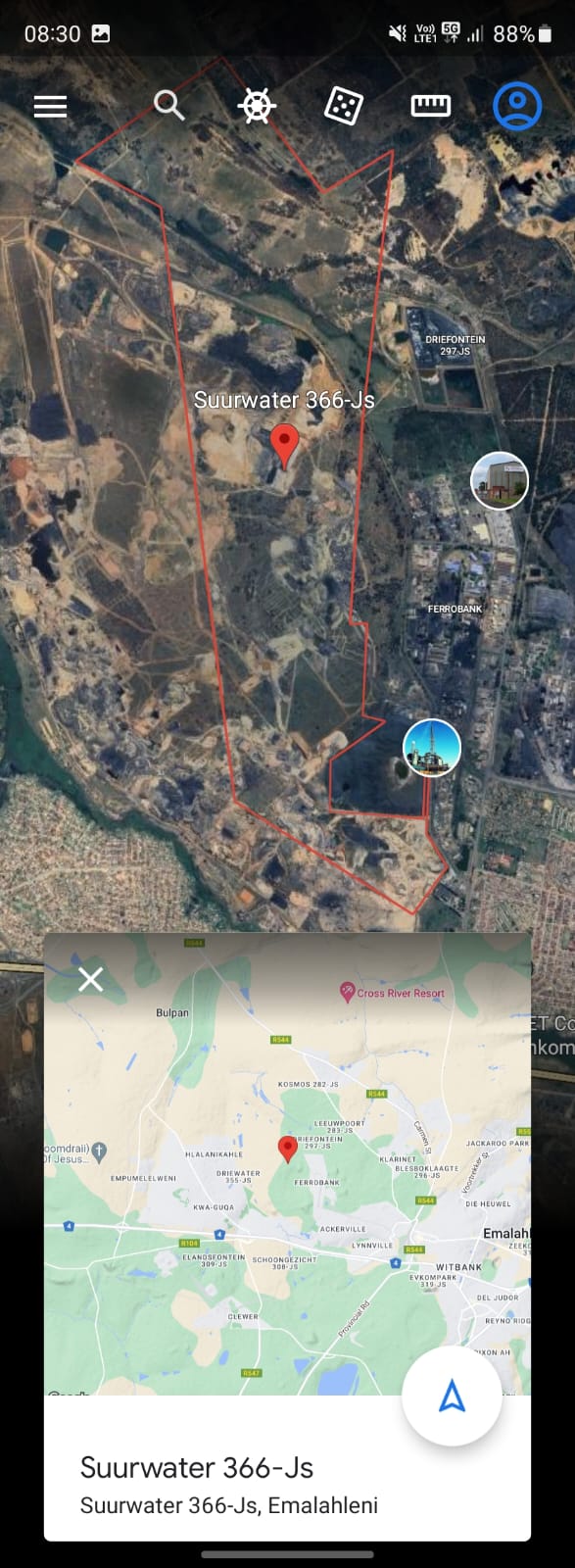

MINING TRAUMA SERIES: Motsepe’s mine managers accused of snubbing DMRE advice to build a ventilation shaft on communal land

MINING TRAUMA SERIES: Motsepe’s mine managers accused of snubbing DMRE advice to build a ventilation shaft on communal land

-

Dear President Patrice Motsepe

Dear President Patrice Motsepe

-

Despite a R71.2 million surplus, KZN Film Commission's officials are under probe for malfeasance

Despite a R71.2 million surplus, KZN Film Commission's officials are under probe for malfeasance

-

Ndlovu moves past 60/40 gender equity hurdle in Mpumalanga cabinet, North-West’s Mokgosi still stuck

Ndlovu moves past 60/40 gender equity hurdle in Mpumalanga cabinet, North-West’s Mokgosi still stuck

-

ANC, Ekurhuleni council accused of dragging feet in disciplining police chief facing allegations of being a sex pest

ANC, Ekurhuleni council accused of dragging feet in disciplining police chief facing allegations of being a sex pest

-

Cryptocurrency scammers leave investors high and dry

Cryptocurrency scammers leave investors high and dry

-

Court dismisses ‘biased’ MEC’s decision to allow mining in a Mpumalanga wetland

Court dismisses ‘biased’ MEC’s decision to allow mining in a Mpumalanga wetland

-

Mpumalanga premier sues newspaper for defamation

Mpumalanga premier sues newspaper for defamation

-

Robert Gumede's consortium lays fraud charge on sugar bidding

Robert Gumede's consortium lays fraud charge on sugar bidding

-

Olympians take a hardline stance against Toyota for global warming and demand action from the IOC

Olympians take a hardline stance against Toyota for global warming and demand action from the IOC

-

Groblersdal police refuse to open a case against VBS-implicated Limpopo MEC

Groblersdal police refuse to open a case against VBS-implicated Limpopo MEC

-

‘Mmabana Foundation is a money-laundering scheme’ – North West DA

‘Mmabana Foundation is a money-laundering scheme’ – North West DA

-

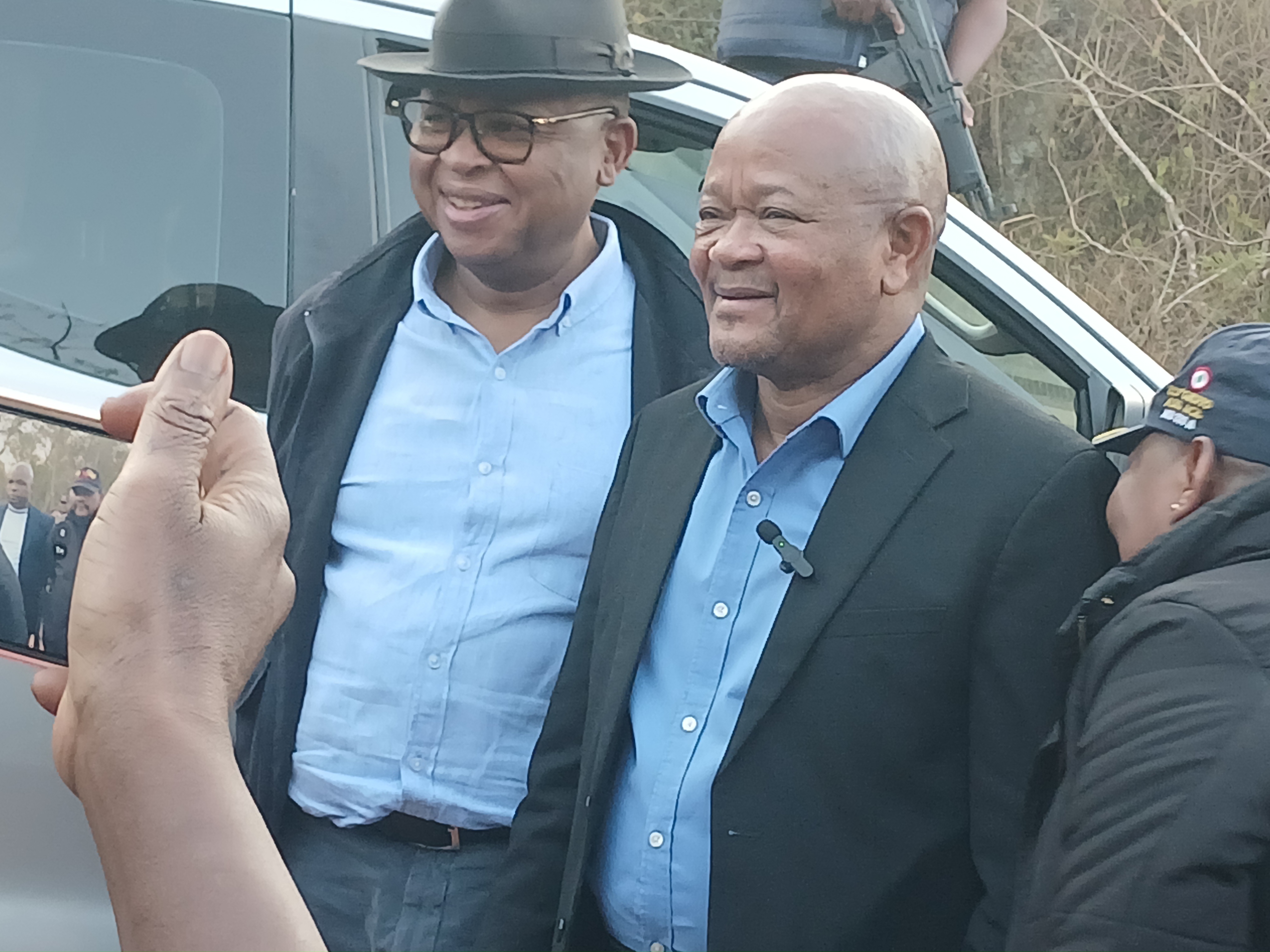

Premier Mandla Ndlovu aiming at politicians’ killers

Premier Mandla Ndlovu aiming at politicians’ killers

-

Brace yourself for an ANC-led coalition – SRF Tracking Poll

Brace yourself for an ANC-led coalition – SRF Tracking Poll

-

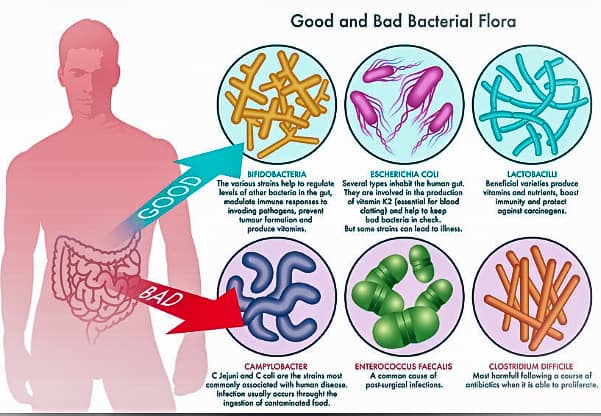

Resistance to antibiotics need special attention to save lives – experts

Resistance to antibiotics need special attention to save lives – experts

-

Disgraced Mozambican company bids afresh for Tongaat assets while Gumede’s consortium takes giant leap to finalise its take over

Disgraced Mozambican company bids afresh for Tongaat assets while Gumede’s consortium takes giant leap to finalise its take over

-

Deputy minister reneges promise to pay R500k debt and then withdraws application to gag businessman and a media house

Deputy minister reneges promise to pay R500k debt and then withdraws application to gag businessman and a media house

-

A contract that no one wants to talk about: Is Mpumalanga health department hiding something?

A contract that no one wants to talk about: Is Mpumalanga health department hiding something?

-

‘I’ll let bygones be bygones’ – Bongo after his discharge from fraud and money laundering case

‘I’ll let bygones be bygones’ – Bongo after his discharge from fraud and money laundering case

-

Mpumalanga’s R150 million expenditure ‘down the drain’

Mpumalanga’s R150 million expenditure ‘down the drain’

-

‘I’m not usurping amakhosi powers’ – Thoko Didiza

‘I’m not usurping amakhosi powers’ – Thoko Didiza

-

Welcome to Zolani Balekwa’s ‘artivism’

Welcome to Zolani Balekwa’s ‘artivism’

-

Being a forensic investigator in Mpumalanga is not for the faint-hearted

Being a forensic investigator in Mpumalanga is not for the faint-hearted

-

‘Courts must not gag MPs’ – pleads convicted Eswatini MP

‘Courts must not gag MPs’ – pleads convicted Eswatini MP

-

UCT research gives thumbs up to home language education

UCT research gives thumbs up to home language education

-

Border between Lesotho and South Africa is not porous but wide open

Border between Lesotho and South Africa is not porous but wide open

-

Municipalities could have spend R2m for councillors to attend ANC shindig

Municipalities could have spend R2m for councillors to attend ANC shindig

-

Sekhukhune municipality mum on lost R46.4 million

Sekhukhune municipality mum on lost R46.4 million

-

‘I’m not appealing’ – says Mandla Msibi after DC suspends him for three years

‘I’m not appealing’ – says Mandla Msibi after DC suspends him for three years

-

Lawyer accused of collapsing biggest citrus estate struck off the roll

Lawyer accused of collapsing biggest citrus estate struck off the roll

-

Mpumalanga premier to convince disillusioned PSL to consider bringing matches to Mbombela stadium

Mpumalanga premier to convince disillusioned PSL to consider bringing matches to Mbombela stadium

-

Northern Cape government wimps out of challenging R3.7m payment to an investigator of land scam

Northern Cape government wimps out of challenging R3.7m payment to an investigator of land scam

-

Ndlovu targets 5% economic growth for job creation in all sectors

Ndlovu targets 5% economic growth for job creation in all sectors

-

Village diesel producer’s breakthrough as he gets his first big order

Village diesel producer’s breakthrough as he gets his first big order

-

Limpopo DPP orders police to reinvestigate false CV case against senior civil servant

Limpopo DPP orders police to reinvestigate false CV case against senior civil servant

-

Municipal manager ordered to stop sewerage spill into river or face a prison sentence

Municipal manager ordered to stop sewerage spill into river or face a prison sentence

-

Vindicated businessman wins first leg of the fight against Master of the High Court to reclaim his assets and cash

Vindicated businessman wins first leg of the fight against Master of the High Court to reclaim his assets and cash

-

SA company set to begin construction of R5.7bn Malawi water project

SA company set to begin construction of R5.7bn Malawi water project

-

Manzini must release details on Mpox – DA

Manzini must release details on Mpox – DA

-

KZN flood victims have a chance to set a precedent by suing fossil-fuel companies for the climate change disaster

KZN flood victims have a chance to set a precedent by suing fossil-fuel companies for the climate change disaster

-

KZN, Mpumalanga governments take steps to resolve chieftaincy disputes

KZN, Mpumalanga governments take steps to resolve chieftaincy disputes

-

Deputy minister Bernice Swarts’s fraud case still under investigation - NPA

Deputy minister Bernice Swarts’s fraud case still under investigation - NPA

-

Msibi to appeal his suspension from the ANC

Msibi to appeal his suspension from the ANC

-

Ramaphosa calls the private sector to invest in major infrastructure projects

Ramaphosa calls the private sector to invest in major infrastructure projects

-

Msibi resigns as MPL as Luthuli House upholds his suspension

Msibi resigns as MPL as Luthuli House upholds his suspension

-

Creecy slammed for being lenient to Sasol

Creecy slammed for being lenient to Sasol

-

Mantashe’s neglect haunts him as mining company drags him to court

Mantashe’s neglect haunts him as mining company drags him to court

-

Forex trading couple’s R2.9m house attached after they defrauded investors

Forex trading couple’s R2.9m house attached after they defrauded investors

-

A 30-second video-recording may save Msibi on misconduct charges

A 30-second video-recording may save Msibi on misconduct charges

-

ANC defends premier against R100 million theft allegations

ANC defends premier against R100 million theft allegations

-

Big construction companies must empower, certify subcontractors to enable their growth - Khato Civils CEO

Big construction companies must empower, certify subcontractors to enable their growth - Khato Civils CEO

-

Teflon KZN mayor promoted to legislature

Teflon KZN mayor promoted to legislature

-

Businessman acquitted in a lengthy trial not yet out of the woods as he fights ‘corrupt’ Master of the High Court officials

Businessman acquitted in a lengthy trial not yet out of the woods as he fights ‘corrupt’ Master of the High Court officials

-

Two Limpopo teachers convicted for doing business with the education department

Two Limpopo teachers convicted for doing business with the education department

-

KZN Cogta MEC locked out of a facility managed by irregularly appointed former mayor’s wife

KZN Cogta MEC locked out of a facility managed by irregularly appointed former mayor’s wife

-

Corruption-fighting politician-cum-civil servant among those whose assets were attached for Covid-19 corruption

Corruption-fighting politician-cum-civil servant among those whose assets were attached for Covid-19 corruption

-

One Mpumalanga MEC to be axed to meet ANC’s gender balance guidelines

One Mpumalanga MEC to be axed to meet ANC’s gender balance guidelines

-

JUST IN: Gen Masemola suspends Mpumalanga commissioner on additional charges of misconduct

JUST IN: Gen Masemola suspends Mpumalanga commissioner on additional charges of misconduct

-

Limpopo capital city’s tale of ‘hiding’ a forensic report, wish to write off R34m due to financial mismanagement

Limpopo capital city’s tale of ‘hiding’ a forensic report, wish to write off R34m due to financial mismanagement

-

Odds stacked against expelled MK Party commander as he tries to remove Zuma

Odds stacked against expelled MK Party commander as he tries to remove Zuma

-

Robert Gumede’s Guma Group, HPX to develop R94.5bn rail network to link Liberia and Guinea

Robert Gumede’s Guma Group, HPX to develop R94.5bn rail network to link Liberia and Guinea

-

Grade 12 cheating rocks Mpumalanga as 150 learners are implicated

Grade 12 cheating rocks Mpumalanga as 150 learners are implicated

-

Botswana averts G7’s plan to certify diamond products in Antwerp

Botswana averts G7’s plan to certify diamond products in Antwerp

-

Controversial former mayor’s wife in KZN ‘given’ another job after fleeing previous employment

Controversial former mayor’s wife in KZN ‘given’ another job after fleeing previous employment

-

How the Matsamo CPA changed wrong perception that blacks cannot run commercial farms

How the Matsamo CPA changed wrong perception that blacks cannot run commercial farms

-

Mahlangu slowly turning things around to revive MEGA

Mahlangu slowly turning things around to revive MEGA

-

Official in Mpumalanga government’s corruption-busting unit dies after being shot 29 times

Official in Mpumalanga government’s corruption-busting unit dies after being shot 29 times

-

Motion to remove a mayor in Mpumalanga aims to portray the ANC as a loser before elections – provincial ANC secretary

Motion to remove a mayor in Mpumalanga aims to portray the ANC as a loser before elections – provincial ANC secretary

-

Limpopo premier Stanley Mathabatha’s ‘henchman’ arrested for faking CV

Limpopo premier Stanley Mathabatha’s ‘henchman’ arrested for faking CV

-

The dire state of the ABC Motsepe League

The dire state of the ABC Motsepe League

-

Dingaan Thobela’s death should serve as a kick in the butt for boxing authorities

Dingaan Thobela’s death should serve as a kick in the butt for boxing authorities

-

Data collected for Census 2022 unfit for purpose - UCT

Data collected for Census 2022 unfit for purpose - UCT

-

Nehawu needs explanation following withdrawal of charges against Limpopo official

Nehawu needs explanation following withdrawal of charges against Limpopo official

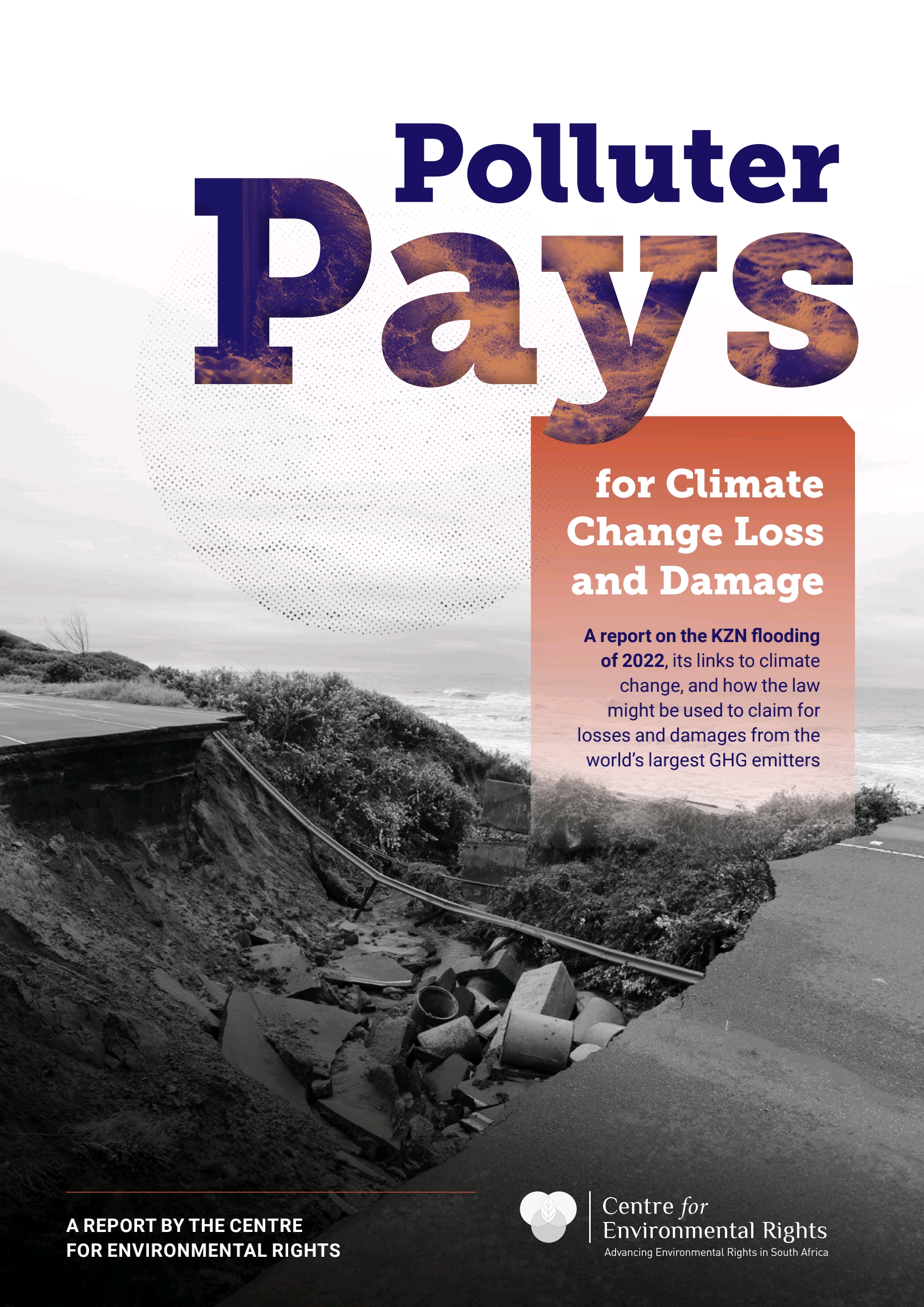

Polluters can be sued for climate change disasters – CER report

Sizwe sama Yende

Individuals and communities in South Africa affected by adverse climate change due to fossil fuels pollution can sue responsible companies for loss and damage.

This is according to a report released by the Centre for Environmental Rights (CER) on March 20. The Polluter Pays for Climate Change Loss and Damage report focuses on the devastating floods in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, in 2022 that left 443 people dead and 48 missing.

The unprecedented floods also damaged 26 000 houses, 600 schools and 84 health facilities. Government was left with a huge bill of R10 billion to repair transportation, communication, water and electrical infrastructure while various sectors recorded major losses - manufacturing (R431m), agriculture (R12.6m), construction (R18m), wholesale and retail (R46m), and warehousing and logistics (R33m).

The United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP 28) reached a milestone last year when it approved the operationalisation of the loss and damage fund and mobilised US$800 million from various countries.

Poor countries in Africa, which contributed less to greenhouse gas emissions, were the most affected by climate change.

POLLUTER PAYS PRINCIPLE

CER researchers and authors of the report believe that the South African law of delict made provisions for claims against carbon majors or polluters.

The National Environmental Management Act 107 of 1999 (NEMA), the report says, also adopted the polluter pays principle which states that: “The costs of remedying pollution, environmental degradation and consequent adverse health effects and of preventing, controlling or minimising further pollution, environmental damage or adverse health effects must be paid for by those responsible for harming the environment.”

The polluter pays principle is an environmental law concept that requires any person or entity that causes pollution to be responsible for the costs of managing such pollution in order to prevent or repair harm caused.

Co-author of the report, Michelle Sithole, said that many of carbon majors (big companies responsible for climate-changing carbon and methane emissions) were based outside South Africa in countries such as Saudi Arabia, Russia, US and the UK.

“In this regard one would set their sights on a foreign carbon major, however the preference would be for one with a South African subsidiary,” Sithole said.

ATTRIBUTION SCIENCE

She said that the application of attribution science would be used to determine if climate change was responsible for the KZN floods or not. “Initial studies by World Weather Attribution have already established a link between the KZN floods and climate change. Attribution science will play an important role in bringing cases against carbon majors/polluters, in showing that it is more probable than not that a carbon major’s actions caused or contributed in a significant way to the KZN floods,” she said.

The report, however, indicated that an initial wave of climate change lawsuits against fossil fuel producers in the mid 2000s, mainly in the USA, were generally not successful.

“That said, the work put into litigation in a developing field is mostly ultimately constructive as evidence resources are built, experts are sourced and legal arguments are expanded and refined. There was a lull in cases brought, until the carbon majors report described above was released. This knowledge, along with the rapid development of attribution science, were among the factors which saw a resurgence of legal action of this type, and there are currently around 60 cases filed against carbon majors.”

KZN CLAIM

The report indicates that compensation in the KZN case could be claimed for losses of public infrastructure, both built and ecological; loss of homes, goods and community infrastructure in both formal and informal settings.

Furthermore, compensation could be claimed for loss of access to services, including healthcare, education and sanitation; damage to food production resources, including small scale farming; physical and mental health impacts, including individual and collective trauma; loss of access to transport and the ability to be economically active; losses to businesses, formal and informal; loss of a sense of place, social cohesion, stability; loss of tangible and intangible heritage; and environmental harm beyond obvious and quantifiable ecosystem services.

“Some of these items reflect the growing exploration of non-economic loss and damage – that which cannot simply be replaced via monetary compensation. It is essential to ensure that the pursuit of redress is informed by the principle of climate justice,” the report says.

“Poor people and communities do not have access to many of the resources required to rebuild their lives, and appropriate forms of compensation and how these are applied must be prioritised.”

POLLUTERS MUST REDRESS CLIMATE CHANGE

The report indicates that the law would need to be developed for polluters to take responsibility for redress for climate change.

The responsible parties could be forced to take part in climate resilient upgrading of informal settlements; climate resilient upgrading of formal infrastructure and public assets; enhancing and replicating interventions such as the community ecologically based adaptation measures; enhancing and replicating the community based flood early warning system and other inclusive disaster response measures; creating green jobs and green economy initiatives that address unemployment and poverty while increasing economic climate resilience.

Scientist and founder of the Climate Accountability Institute, Richard Heede, along with Professor Marco Grasso, released a paper in 2023 which makes the case for reparations claims against the top 20 carbon majors.

The research indicates that the cumulative cost of climate damages (based on loss of GDP) for the period 2025 to 2050 is broadly estimated at US$99 trillion.

The paper posits apportioning this amount equally across: fossil fuel producers; consumers who use the products; and the political authorities who should be taking action and failing to do so.